This is the second of several posts walking through an implementation of the Enigma cipher in code.

Thanks to the website of the late Tony Sale for providing a wealth of detailed, accurate information entirely free of graduate level mathematics, and includes some very clear examples for luddites like me who need everything spelled out really clearly.

The Goal

The goal of analyzing the Enigma machine is to better understand the workings of a device that played an important role in the history of computing. It is also an excellent system to better understand some of the design decisions we make when creating a code representation of a problem.

The intention is to replicate some of the encryption mechanisms of the original Enigma. From the Part 1 post, which covered more about how Enigma works, we have built up a basic understanding of what each step does. In this post we discuss how to implement this functionality.

The basic idea is to start with a plaintext input (typed by the operator) and apply a rotating cripher to encrypt it, resulting in a ciphertext output:

_________

| |

PLAINTEXT ---> | ENIGMA | ----> CIPHERTEXT

|_________|

Function or Object?

One of the first decisions typically made (sometimes implicitly) is whether to implement the Enigma as a function or an object. Is the Enigma a noun, or a verb?

The Noun Approach

Programming in a language like Java or C++, the noun approach seems perfectly natural: start with an Enigma object (the noun), and create more objects to represent more of the nouns (the switchboard, the rotor wheels, and the reflector). Each component is modeled as a black box function taking a character in and returning a character out. Each component stores and organizes information important for it to perform its particular transformation. For example, the rotors would store the scrambled version of the alphabet that they implement, while the switchboard and the reflector would store the connected letter pairs.

This approach reflects the kind of engineering approach that was taken to the design of the Enigma: many simple components, working together in concert, result in a more complex integrated system.

But one of the reasons the Enigma machine is an interesting system for implementing in code is because of the simplicity of the mechanical operations performed. This can help identify where a person actually begins the software design process. If the design process starts with one foot in the world of objects already, the object approach will be adopted by default.

With this approach, we are reshaping our data structures to fit the problem. This makes the implementation more modular and the driver easier to read at a high level. However, reshaping the data structures to fit the problem and our abstraction of it can lead to more inefficient code and implementations.

The Verb Approach

Instead, we can start by examining the encryption process itself - the verb of encryption. The action of encryption consists of elementary steps - swapping out two characters. Each of these actions is simple enough that it can be implemented using built-in string manipulation methods, and all of the quantities being stored are likewise simple enough that no exotic data structures are required.

The verb approach requires considering the problem up-front (possibly recasting it in different terms), and thinking through the actions involved in order to best utilize simple, built-in data structures and functionality.

With this approach we essentially reshape the problem to fit our data structures, rather than the other way around.

Applying the Verb Approach to the Rotors

Rotors

To get a better sense of what the verb approach looks like, let's look at the Enigma rotors.

Each rotor implements a particular permutations of the 26 letters of the alphabet:

This is equivalent to matching up two strings. To make things slightly more concrete, let's look at Rotor I, nicknamed Royal (due to the location of its notch at the letter R), implemented the scrambled alphabet "EKMFLGDQVZNTOWYHXUSPAIBRCJ". With an offset of 0, this would therefore implement the following shift:

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

EKMFLGDQVZNTOWYHXUSPAIBRCJ

This operation, when broken down, is trivial: we are matching two characters from two strings, both at a particular location.

Starting with a char, representing the character coming into the rotor,

we can perform a two-step operation:

1. Get the index of the incoming character in the normal alphabet ABCDEF....

2. Get the corresponding character at that index in the scrambled alphabet EKMFLG....

We will also need to perform the reverse operation when we return the signal back through the machine from the reflector. In that case, we're actually performing the opposite lookup, for the same wheel:

EKMFLGDQVZNTOWYHXUSPAIBRCJ

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ

When we were going through Rotor I the first time, A became E, and E became L; when going through in reverse, E now becomes A, and L now becomes E.

The procedure can also be reversed:

1. Get the index of the incoming character in the scrambled alphabet EKMFLG....

2. Get the corresponding character at that index in the normal alphabet ABCDEF....

Applying this multiple times in sequence applies multiple scrambles and replicates multiple rotors.

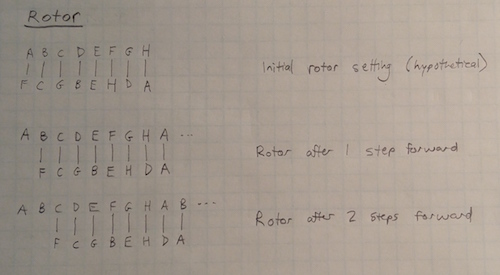

Example of Verb Approach: Rotor Rotation

One of the reasons an object-oriented approach may seem natural, besides the chosen language suggesting it, is because the Enigma is an object with a state. Objects provide a natural way of representing things with an internal state, or information specific to that entity and required for its operation.

For this reason, it may seem at first blush that the Engima requires an object-oriented implementation. However, we can continue with our verb-centric thinking, and examine how the operations change when the wheels are rotated.

After 2 rotations:

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZAB

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

EKMFLGDQVZNTOWYHXUSPAIBRCJ

After 4 rotations:

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZABCD

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

EKMFLGDQVZNTOWYHXUSPAIBRCJ

As the wheels rotate, we are still performing the same index lookup operations, we are just rotating each scrambled alphabet by one character. Again, this is a trivial operation that is probably built in for string types.

Rotor Pseudocode

Putting all of this together, here's pseudocode for a single forward transformation by an Engima rotor:

define plaintext message

define normal alphabet and scrambled alphabet

for each character in plaintext message:

get index of input character in normal alphabet

get new character at that index in scrambled alphabet

concatenate transformed character to ciphertext message

Because the Enigma has multiple rotors, we also want pseudocode for multiple rotors:

define plaintext message

define normal alphabet and scrambled alphabets

for each character in plaintext message:

for each scrambled alphabet:

get index of character in normal alphabet

get new character at that index in scrambled alphabet

replace character with new character

concatenate transformed character to ciphertext message

Likewise, to apply multiple rotations in reverse, we just swap the alphabets out:

define plaintext message

define normal alphabet and scrambled alphabets

for each character in plaintext message:

for each scrambled alphabet:

get index of character in scrambled alphabet

get new character at that index in normal alphabet

replace character with new character

concatenate transformed character to ciphertext message

A More Complete Enigma Pseudocode

To combine these operations, or add additional operations, we just add them before concatenating the final transformed character to the ciphertext message. Thus, a more complete pseudocode would include other steps:

define plaintext message

define normal alphabet and scrambled alphabets

for each character in plaintext message:

# Apply switchboard transformation

# Apply forward rotor transformation

for each scrambled alphabet:

get index of character in normal alphabet

get new character at that index in scrambled alphabet

replace character with new character

# Apply reflector transformation

# Apply reverse rotor transformation

for each scrambled alphabet:

get index of input character in scrambled alphabet

get new character at that index in normal alphabet

replace character with new character

# Apply switchboard transformation

concatenate transformed character to ciphertext message

Now let's cover the switchboard and reflector transformations.

The Switchboard

We can take the same verb-based approach to the switchboard as we took for the rotors. When we think through the actual operation being performed by the switchboard, it is even simpler than the operation performed by the rotor wheels. We have pairs of letters, and we are simply looking for one letter in a pair, and swapping it out with the other letter in the pair. In the case of the switchboard, Enigma operators utilized 7-10 wires to connect pairs of letters; the remaining letters were unchanged. So the switchboard step is very simple:

define plaintext message

define list of switchboard swap pairs

for each character in message:

for each pair in swap pairs:

if character in swap pair, swap its value

add character to ciphertext

That's it! No need for a reverse function, since the swap procedure is symmetric. (Note that if there is no wire connecting a letter to another letter, there is no swap operation, and the character is added to the ciphertext directly.)

The Reflector

The reflector pseudocode looks identical to the switchboard pseudocode, except the reflector defines pairings for all 13 posible letter pairs, instead of only 7-10.

define plaintext message

define list of reflector swap pairs

for each character in message:

for each pair in swap pairs:

if character in swap pair, swap its value

add character to ciphertext

Again, no need for a reverse version, since the reflector is a symmetric transformation.

Nearing a Complete Enigma Pseudocode

Almost there. We have one more thing going on - those rotor wheels are moving. Add the "increment rotor wheels" verb, and define that below.

define plaintext message

define normal alphabet and scrambled alphabets

define list of switchboard swap pairs

define list of reflector swap pairs

for each character in plaintext message:

# Apply switchboard transformation

for each pair in switchboard swap pairs:

if character in swap pair, swap its value

# Apply forward rotor transformation

for each rotor/scrambled alphabet:

get index of character in normal alphabet

get new character at that index in scrambled alphabet

replace character with new character

# Apply reflector transformation

for each pair in reflector swap pairs:

if character in swap pair, swap its value

# Apply reverse rotor transformation

for each scrambled alphabet:

get index of input character in scrambled alphabet

get new character at that index in normal alphabet

replace character with new character

# Apply switchboard transformation

for each pair in switchboard swap pairs:

if character in swap pair, swap its value

concatenate transformed input character to ciphertext message

increment rotor wheels

Incrementing the Rotor Wheels

Each rotor wheel has a notch located at a particular letter. The wheels were identified by the letter on which the notch was located (Rotor I was "Royal" because the notch was located at "R", and so on).

The notches were designed to catch on the notches of other rotor wheels, in such a way that the wheels would turn together periodically. The right-most wheel would rotate once per keypress. Once per 26 letters (if S = 26), the notch would catch the notch of the next rotor over and advance it forward by 1 letter. It was this mechanism that kept the machine constantly skipping through the space of possible keys, mapping each character to each other character, with one distinct key (alphabet scramble) used per letter of the message.

To increment the wheels in pseudocode:

function increment rotors:

for each rotor/scrambled alphabet, left to right:

get index of left notch in left alphabet

get index of right notch in right alphabet

if left index equals right index:

cycle left alphabet forward 1 character

cycle right-most alphabet forward 1 character

Enigma Pseudocode

Almost there. We have one more thing going on - those rotor wheels are moving. Add the "increment rotor wheels" verb, and define that below.

define plaintext message

define normal alphabet and scrambled alphabets

define list of switchboard swap pairs

define list of reflector swap pairs

for each character in plaintext message:

# Apply switchboard transformation

for each pair in switchboard swap pairs:

if character in swap pair, swap its value

# Apply forward rotor transformation

for each rotor/scrambled alphabet:

get index of character in normal alphabet

get new character at that index in scrambled alphabet

replace character with new character

# Apply reflector transformation

for each pair in reflector swap pairs:

if character in swap pair, swap its value

# Apply reverse rotor transformation

for each scrambled alphabet:

get index of input character in scrambled alphabet

get new character at that index in normal alphabet

replace character with new character

# Apply switchboard transformation

for each pair in switchboard swap pairs:

if character in swap pair, swap its value

concatenate transformed input character to ciphertext message

# Increment rotor wheels

for each rotor/scrambled alphabet, left to right:

get index of left notch in left alphabet

get index of right notch in right alphabet

if left index equals right index:

cycle left alphabet forward 1 character

cycle right-most alphabet forward 1 character

Sources

- "The Enigma Cipher". Tony Sale and Andrew Hodges. Publication date unknown. Accessed 18 March 2017. <https://web.archive.org/web/20170320081639/http://www.codesandciphers.org.uk/enigma/index.htm>