Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Complete and Reduced Residue Systems

- Euler's Totient Function

- Calculating the Totient Function by Hand

Introduction

Today we're going to delve into a little bit of number theory.

In number theory, we are usually dealing with modular arithmetic - expressions of the form:

or

The mod indicates we're doing modular arithmetic, which is (formally) an algebraic system called a ring, which consists of the integers 0 through m.

An analogy to modular arithmetic is the way that the sine and cosine function "wrap around," and

On a ring, this happens with the integers. So, for example,

Modular arithmetic uses the \(\equiv\) symbol, and not the \(=\) symbol, because we can't manipulate the left and right side using normal rules of algebra - solving equations on a ring requires some care.

The value of \(m\) need not be prime, generally, but if it is, we have some special properties that hold.

Complete and Reduced Residue Systems

Consider the ring of integers \(\mod 10\), which consists of the numbers

This is called the complete residue system mod 10. If we want to solve an equation like

we would normally just divide both sides by 2. But because of the "mod 10" we have to be a bit more careful. Dividing by 2 is just a way of saying, we want to multiply 2 by some number that will make 2 into 1.

However, because 2 is a factor of 10, there is no number in the complete residue system that will yield 1 mod 10 when we multiply it by 2:

The same difficulty appears if we try and solve an equation like

for the same reason - 5 is a factor of 10, so it has no inverse mod 10.

Contrast that with solving an equation like

which, because 3 does not share any factors with 10, means we can find a number such that 3 times that number yields 1 mod 10:

so we can solve the equation by multiplying both sides by 7, the inverse of 3:

We can resolve this by creating a reduced residue system, which is a set of integers that have inverses mod 10. The reduced residue system consists of integers that

- Have no common factors with the ring size \(m\)

- Have no two elements that are congruent \mod m

So a reduced residue system \(\mod 10\) could be, for example,

(other reduced residue systems are possible as well).

It is important to note that we do not include 0, in general, because 0 shares all factors with \(m\) - that is, every number in the complete residue system divides 0, so the greatest common factor of \(0\) and \(m\) is \(m\) and not 1!

(The only exception to this rule is \(m=1\), but this is a trivial case, since every integer is congruent mod 1.)

The reduced residue system has the property that any number in the complete residue system can be generated from the reduced residue system via addition.

Further, the size of the reduced residue system can be expressed using a function called the Euler totient function, denoted \(\phi(m)\). The totient function quantifies the number of integers less than \(m\) that are relatively prime with \(m\) (that is, two numbers such that the greatest common factor, denoted with the shorthand \((a,m)\), is 1).

Euler's Totient Function

Euler's totient function, \(\phi(m)\), turns out to be an extremely useful quantity in number theory. It also provides a quantitative measure of how divisible a number is. Take the two numbers 960 and 961 as examples:

from this, we can see that 960 has many more factors than 961. Here are their prime factorizations:

This means that the ring of integers mod 960 will have far more congruences that cannot be solved compared to the ring of integers mod 961.

Historical Note: The notation \(\phi(n)\) was first used by the mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauss in his incredible book Disquisitiones Arithmeticae, an important historical textbook that focused on gathering all of the results known to that point about number theory in a single work. (Gauss did omit the parenthesis, however, writing the totient function simply as \(\phi n\).)

Calculating the Totient Function by Hand

It may be obvious that the totient function is simple to compute using a computer; but the question naturally arises: can we compute totient functions for large integers by hand?

It turns out we can - we just need to be able to factor the number in question. (Note that this requirement is true generally; see the section on RSA Cryptography in a post to follow).

Let's first illustrate some rules for computing the totient function of composite numbers with some simple examples.

Totient Property: Prime Power

The first useful property is computing the totient function of a number that is a prime number raised to some power. Let's take the simple example of \(81 = 9^2 = 3^4\). We know that any number that shares factors with 81 is a multiple of 3 less than or equal to 81, which is the set of numbers

and there are \(3^{4-1}\) of these numbers. Thus, of all of the integers from \(1\) to \(3^4\), there are \(3^3\) of them that are not relatively prime with \(3^4\). So the totient function can be written:

In general, if we are considering the totient function of a prime power \(p^k\), we can write the totient function as

Totient Property: Product of Primes

If we take a composite number like 20, we can split the totient function of 20 into the product of the totient function of the factors of 20:

which is, indeed, the value of \(\phi(20)\). However, this does not hold generally, as we can see from computing the totient of 50:

In fact, the value of \(\phi(50)\) is 20, not 16! The problem is with our choice of factors, 5 and 10. These two numbers share a common factor of 5, meaning their totient functions do not account for all of the numbers that will be relatively prime with 50.

To fix this, we can further break down 50 into its prime factorization, and compute the totient function of those primes:

which gives us the correct result of 20.

Generalizing this rule, we can say that we can break down the totient function of a product of two numbers \(s \times t\) into the product of totient functions \(\phi(s)\) and \(\phi(t)\) only if the greatest common factor between \(s\) and \(t\) is 1.

Totient Example

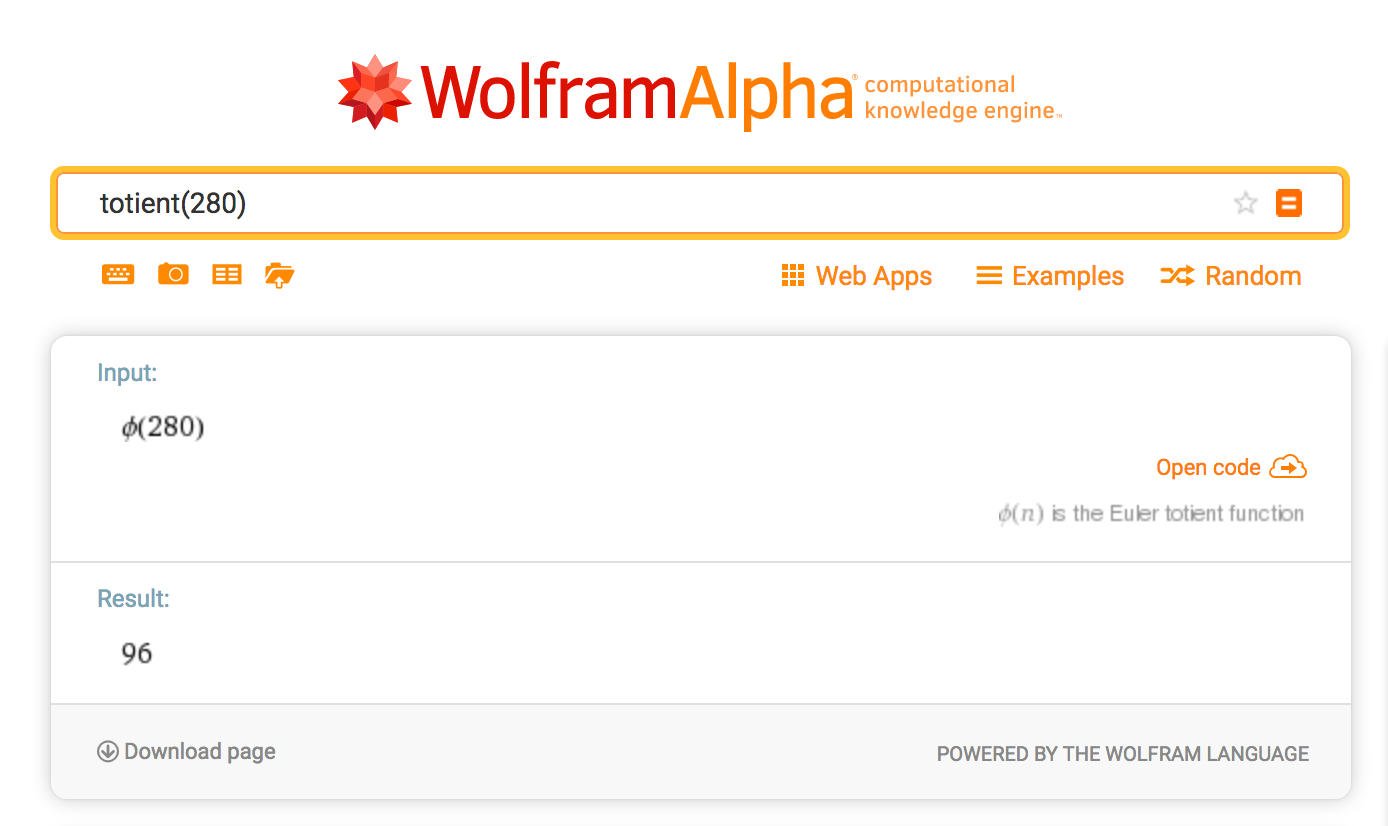

Let's consider the following example: suppose we wish to compute

We can start by recognizing some factors of 280 - we can pull out the factors 7 and 4, and 2 and 5. These can be further factored to yield the prime factorization of 280:

Now we can use the property that the totient function of an integer \(m\) can be expressed as the product of the totient functions of the factors of \(m\). So we can write \(\phi(280)\) as any of the following equivalent expressions:

Using the second expression, we know that

for an overall totient function value of

which is indeed the correct result: