Table of Contents

- Background: Huh?

- N Queens Problem

- N Queens Solution

- Head to Head: Walltime vs. Number of Queens

- Perl Profiling

- Perl Profiling Results

- Java Profiling

- Java Profiling Results

- Head to Head: Walltime vs. Number of Solutions Tested

- Apples and Oranges

- Sources

Summary

In this post, we describe an implementation of the N Queens Problem, which is a puzzle related to optimization, combinatorics, and recursive backtracking. The puzzle asks: how many configurations are there for placing 8 queens on a chessboard such that no queen can attack any othr queen?

This problem was implemented in Perl and in Java, the solution results were timed, and the codes were profiled. While Perl is an interpreted language, and is therefore fully expeted to be much slower than Java (which indeed it is), it is still useful to compare the performance between these two codes to gain an appreciation for the advantages and disadvantages to both approaches.

Background: Huh?

Recently I read an (11 year old) article by Steve Yegge entitled "Execution in the Kingdom of Nouns." In it, Steve describes the way that in Java, "Classes are really the only modeling tool Java provides you. So whenever a new idea occurs to you, you have to sculpt it or wrap it or smash at it until it becomes a thing, even if it began life as an action, a process, or any other non-'thing' concept."

The article inspired me to try on this verb-oriented mode of thinking in a more... active way. Prior experiences with OCaml were confusing, and Haskell continues to evade me, so it was easier to dust off old Perl skills than learn enough Haskell or Ocaml to solve N queens problem. Perl was the next-closest verb-oriented "scripting" language.

I was also familiar with the N queens problem, since I'm a programming instructor (I'll let you guess which language), and it seemed like a nice problem for both noun-based and verb-based approaches. But it also meant I had to learn enough Perl to solve the N queens problem.

...or, use the Perl solution to the N queens problem from Rosetta Code.

Right...

So here's the plan: study a verb-oriented implementation of this canonical, deceptively subtle programming problem in Perl; translate it into a verb-oriented Java program; and run the two head-to-head, using a profiler to understand the results.

N Queens Problem

The N queens problem predates computers - it's a chess puzzle that asks: how many ways can you place 8 queens on a chessboard such that no queen can attack any other queen?

The number of possible configurations of queens on a chessboard is 64 pick 8, or

Here's that calculation in Python:

>>> import numpy as np

>>> np.prod(range(64-8+1,64+1))

178462987637760

That's bigger than the net worth of most U.S. Presidents!

If we implemented a dumb brute-force solution that tested each of these configurations, we'd be waiting until the heat death of the universe.

Fortunately, as we place queens on the board we can check if it is an invalid placement, and rule out any configurations that would follow from that choice. As long as we are making our choices in an orderly fashion, this enables us to rule out most of the nearly 10 quadrillion possibilities. If we place queens column-by-column and rule out rows where there are already queens, by keeping track of where queens have already been placed, we can reduce the number of possible rows by 1 with each queen placed. The first queen has 8 possible rows where it can be placed, the second queen has 7 possible rows (excluding the row that the first queen was placed on), and so on. The number of possiblities is:

A big improvement! Here's that calculation in Python:

>>> def fact(n):

... if(n==1):

... return 1

... else:

... return n*fact(n-1)

...

>>> fact(8)

40320

This still-large number of possibilities can be further reduced by using the same procedure, but checking for invalid rows based on the diagonal squares that each already-placed queen attacks. This covers each precondition for a solved board, and allows the base case of the recursive backtracking method to be as simple as, "If you've reached this point, you have a valid solution. Add it to the solutions bucket."

Now, let's get to the solution algorithm.

N Queens Solution

As a recap, we dusted off our Perl skills to utilize an N queens solution in Perl from Rosetta Code.

Here's the pseudocode:

explore(column):

if last column:

# base case

add to solutions

else:

# recursive case

for each row:

if this is a safe row:

place queen on this row

explore(column+1)

remove queen from this row

Both codes use integer arrays to keep track of where queens are placed. Solutions are stringified version of these arrays, consisting of 8 digits.

Perl Solution

After looking at the Rosetta Code solution for a (long) while and marking it up with comments to understand what it was doing,

I decided it was precisely the kind of verb-oriented solution I wanted to test out to compare Perl and Java.

It uses no objects, but instead relies on fast built-in data structures (arrays),

for loop expansion (only for my $i (1 .. $N), no for($i=1; $i<=$N; $i++)),

and basic integer math. The cost of solving the problem comes down to basic indexing and array access.

This is the kind of solution I imagine a human calculator like Alan Turing or John Von Neuman looking at, nodding, and saying, "Makes sense! (And by the way the answer is 92.)"

#!/usr/bin/perl

# Solve the N queens problem

# using recursive backtracking.

#

# Author: Charles Reid

# Date: March 2017

# Create an array to store solutions

my @solutions;

# Create an array to store where queens have been placed

my @queens;

# Mark the rows already used (useful for lookup)

my @occupied;

# explore() implements a recursive, depth-first backtracking method

sub explore {

# Parameters:

# depth : this is the argument passed by the user

# First argument passed to the function is $depth

# (how many queens we've placed on the board),

# so use shift to pop that out of the parameters

my ($depth, @diag) = shift;

# Explore is a recursive method,

# so we need a base case and a recursive case.

#

# The base case is, we've reached a leaf node,

# placed 8 queens, and had no problems,

# so we found a solution.

if ($depth==$board_size) {

# Here, we store the stringified version of @queens,

# which are the row numbers of prior queens.

# This is a global variable that is shared across

# instances of this recursive function.

push @solutions, "@queens\n";

return;

}

# Mark the squares that are attackable,

# so that we can cut down on the search space.

$#diag = 2 * $board_size;

for( 0 .. $#queens) {

$ix1 = $queens[$_] + $depth - $_ ;

$diag[ $ix1 ] = 1;

$ix2 = $queens[$_] - $depth + $_ ;

$diag[ $ix2 ] = 1;

}

for my $row (0 .. $board_size-1) {

# Cut down on the search space:

# if this square is already occupied

# or will lead to an invalid solution,

# don't bother exploring it.

next if $occupied[$row] || $diag[$row];

# Make a choice

push @queens, $row;

# Mark the square as occupied

$occupied[$row] = 1;

# Explore the consequences

explore($depth+1);

# Unmake the choice

pop @queens;

# Mark the square as unoccupied

$occupied[$row] = 0;

}

}

$board_size = 8;

explore(0);

print "total ", scalar(@solutions), " solutions\n";

Java Solution

Starting with the Rosetta Code solution in Perl, I translated the algorithm into Java, sticking as closely as possible to the Way of the Verb. I replicated the solution in Java with a minimal amount of object-oriented-ness. A Board class simply wraps the same set of arrays and array manipulations that the Perl solution implements directly. These constitute the lookahead check for safe places to put the queen.

The Java solution implements a static class containing a Linked List to store solutions. This is the only use of non-array objects and has a trivial impact on the solution walltime.

(Verbatim code not included for length.)

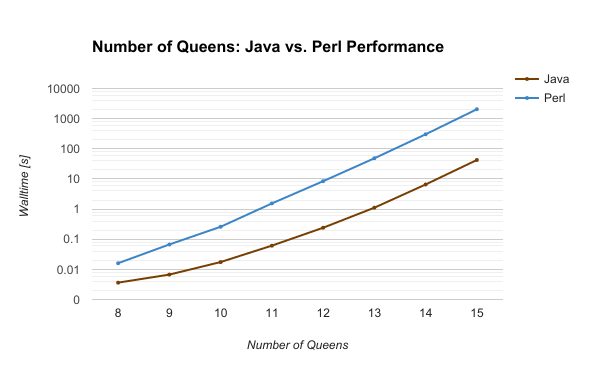

Head to Head: Walltime vs. Number of Queens

-----------------------------------------------

| NQueens | Nsolutions | Java [s] | Perl [s] |

|---------|------------|-----------|----------|

| 8 | 92 | 0.003 | 0.016 |

| 9 | 352 | 0.006 | 0.067 |

| 10 | 724 | 0.017 | 0.259 |

| 11 | 2680 | 0.061 | 1.542 |

| 12 | 14200 | 0.240 | 8.431 |

| 13 | 73712 | 1.113 | 48.542 |

| 14 | 365596 | 6.557 | 303.278 |

| 15 | 2279184 | 42.619 | 2057.052 |

-----------------------------------------------

Java smokes Perl.

Initially I was using the Unix time utility to time these two,

and it seemed to be close for smaller problem sizes (N=9 or smaller) -

Perl would start up and run faster than Java, measured end-to-end.

But when you time the program by using timers built into the language,

it removes some of the overhead from the timing comparisons,

and Java becomes the clear winner.

We can dig deeper and understand this comparison better by using some profiling tools.

Perl Profiling

I profiled Perl with Devel::NYTProf ,

an excellent Perl module available here on Cpanm.

More details about the profiling tools I used for Perl are on the charlesreid1 wiki at Perl/Profiling.

To run with Devel::NYTProf, use `cpanm:

$ cpanm Devel::NYTProf

Now you can run Perl with Devel::NYTProf by doing:

$ perl -d:NYTProf nqueens.pl

This results in a binary output file called nytprof.out that can be processed with several

NYTProf post-processing tools. Use the CSV file tool to begin with:

$ nytprofcsv nytprof.out

This puts the CSV file in a folder called nytprof/.

Perl Profiling Results

The CSV output of the NYTProf module gives a breakdown of the amount of time spent in each method call, how many times it was called, and how much time per call was spent. From this we can see the busiest lines are the lines accessing the arrays, and looping over the rows. This is confirmation that this algorithm is testing the performance of the arrays, and confirms the N queens problem is profiling Perl's core performance with its built-in data structures.

The profiling results of the 11 queens problem are shown below.

# Profile data generated by Devel::NYTProf::Reader

# Version: v6.04

# More information at http://metacpan.org/release/Devel-NYTProf/

# Format: time,calls,time/call,code

0.000238,2,0.000119,use Time::HiRes qw(time);

0.000039,2,0.000019,use strict;

0.000491,2,0.000246,use warnings;

0.000021,1,0.000021,my $start = time;

0.010338,2680,0.000004,push @solutions, "@queens\n";

0.009993,2680,0.000004,return;

0.186298,164246,0.000001,$#attacked = 2 * $board_size;

0.150338,164246,0.000001,for( 0 .. $#queens) {

0.675523,1.26035e+06,0.000001,$attacked[ $ix2 ] = 1;

1.242624,164246,0.000008,for my $row (0 .. $board_size-1) {

0.267469,166925,0.000002,explore($depth+1);

0.125272,166925,0.000001,$occupied[$row] = 0;

0.000002,1,0.000002,explore(0);

0.000011,1,0.000011,my $duration = time - $start;

0.000075,1,0.000075,print "Found ", scalar(@solutions), " solutions\n";

0.000050,1,0.000050,printf "Execution time: %0.3f s \n",$duration;

One of the more interesting pieces of information comes from several lines

populating the squares that are on the diagonals with other queens ($attacked):

# Format: time,calls,time/call,code

0.186298,164246,0.000001,$#attacked = 2 * $board_size;

The second column gives the number of times this line is executed - 164,246. This is actually the number of solutions that are tried, excluding the deepest depth of the tree (the base recursive case).

The Java profiler will show us that Java explores the exact same number of solutions, which is confirmation that these tests are comparing the two languages on equal footing.

Java Profiling

More details about the profiling tools I used for Java are on the charlesreid1 wiki at Java/Profiling

I profiled Java with two tools, the Java Interactive Profiler (JIP) and the HPROF tool that Oracle provides with Java.

No special compiler flags are needed, so compile as normal:

$ javac NQueens.java

If you are profiling with JIP, you want the JIP jar, as described on the wiki: Java/Profiling

Then run Java with the -javaagent flag:

$ export PATH2JIP="${HOME}/Downloads/jip"

$ java -javaagent:${PATH2JIP}/profile/profile.jar NQueens

This results in a profile.txt file with detailed profiling information

(an example is shown below).

The HPROF tool likewise requires no special compiler flags. It can be run with various options from the command line. Here's a basic usage of HPROF that will reduce the amount of output slightly, making the size of the output file a little smaller:

$ java -agentlib:hprof=verbose=n NQueens

This dumps out a file called java.hprof.txt that contains a significant amount of information.

The most useful, though, is at the end, so use tail to get a quick overview of the results:

$ tail -n 100 java.hprof.txt

Java Profiling Results

The profiling results from JIP for the 11 queens problem are shown below.

+----------------------------------------------------------------------

| File: profile.txt

| Date: 2017.03.19 19:34:18 PM

+----------------------------------------------------------------------

+--------------------------------------+

| Most expensive methods summarized |

+--------------------------------------+

Net

------------

Count Time Pct Location

===== ==== === ========

166926 909.5 82.2 NQueens:explore

164246 55.6 5.0 Board:getDiagAttacked

166925 41.4 3.7 Board:unchoose

166925 40.7 3.7 Board:choose

164246 31.0 2.8 Board:getOccupied

1 18.2 1.6 NQueens:main

2680 7.3 0.7 Board:toString

2680 2.3 0.2 SolutionSaver:saveSolution

1 0.2 0.0 SolutionSaver:nSolutions

1 0.1 0.0 SolutionSaver:<init>

1 0.0 0.0 Board:<init>

From this output we can see that the method getDiagAttacked, which is called each time we check a solution in the recursive case, is called 164,246 times - exactly the same number of solutions that the Perl profiler showed. One of the downsides of the JIP profiler is that it only gives high-level profiling information about methods and classes - it stops there.

Fortunately, however, the HPROF tool picks up where JIP leaves off. The HPROF tool makes the program much slower but yields a huge amount of information. In addition to an enormous heap dump of all objects appearing on Java's heap at any point, it also shows where the time was spent in the low-level methods.

SITES BEGIN (ordered by live bytes) Sun Mar 19 19:34:21 2017

percent live alloc'ed stack class

rank self accum bytes objs bytes objs trace name

1 86.01% 86.01% 10510976 164234 10510976 164234 300462 int[]

2 1.93% 87.94% 235840 2680 235840 2680 300467 char[]

3 1.09% 89.03% 133320 1515 133320 1515 300465 char[]

4 1.07% 90.11% 131200 8 131200 8 300263 char[]

5 1.05% 91.16% 128640 2680 128640 2680 300464 char[]

6 1.04% 92.20% 127560 1313 127560 1313 300010 char[]

7 0.76% 92.96% 92728 1009 92728 1009 300000 char[]

8 0.54% 93.50% 65664 8 65664 8 300260 byte[]

9 0.53% 94.02% 64320 2680 64320 2680 300468 java.util.LinkedList$Node

10 0.53% 94.55% 64320 2680 64320 2680 300466 java.lang.String

SITES END

HPROF tells us that over 86% of the time spent on this program was spent accessing integer arrays. Again, confirmation that we are getting a fair measurement of Java's performance with a core data type, the integer array.

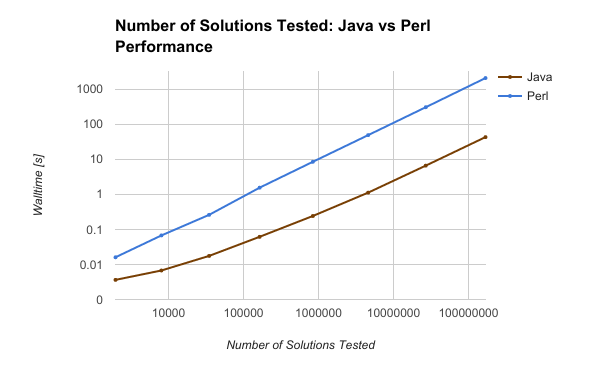

Head to Head: Walltime vs. Number of Solutions Tested

Using the results of the profilers from each N queens problem, N = 8 .. 15,

I extracted the total number of solutions tried, and confirmed that these numbers were the same

between Java and Perl for each of the problem sizes.

Here is a table of the number of solutions found, and number of solutions tried, versus problem size:

-------------------------------------------------------------

| NQueens | Nsolutions | Ntested | Java [s] | Perl [s] |

|---------|------------|-------------|-----------|----------|

| 8 | 92 | 1965 | 0.003 | 0.016 |

| 9 | 352 | 8042 | 0.006 | 0.067 |

| 10 | 724 | 34815 | 0.017 | 0.259 |

| 11 | 2680 | 164246 | 0.061 | 1.542 |

| 12 | 14200 | 841989 | 0.240 | 8.431 |

| 13 | 73712 | 4601178 | 1.113 | 48.542 |

| 14 | 365596 | 26992957 | 6.557 | 303.278 |

| 15 | 2279184 | 168849888 | 42.619 | 2057.052 |

-------------------------------------------------------------

When the wall time for Java and Perl are plotted against the number of solutions tested, an interesting trend emerges: the two scale the same way, with a fixed vertical offset.

While this is proving what we already knew, that a compiled language beats a scripted language every time, it also provides proof Perl can scale as well as Java - it just takes significantly more overhead and time per statement.

Why Java Beat Perl

Compiled languages are turned into bytecode and pre-optimized for the processor.

Perl is a scripted and interpreted language, like Python, evaluated piece by piece.

So, we didn't learn anything surprising. But we did find an interesting result - Perl can scale as well as Java in its implementation of the N queens recursive backtracking algorithm.

Sources

-

"Execution in the Kingdom of Nouns". Steve Yegge. March 2006. Accessed 18 March 2017. <https://web.archive.org/web/20170320081755/https://steve-yegge.blogspot.com/2006/03/execution-in-kingdom-of-nouns.html>

-

"N-Queens Problem". Rosetta Code, GNU Free Documentation License. Edited 6 March 2017. Accessed 21 March 2017. <https://web.archive.org/web/20170320081421/http://rosettacode.org/wiki/N-queens_problem>

-

"nqueens.pl". Charles Reid. Github Gist, Github Inc. Edited 20 March 2017. Accessed 20 March 2017. <https://gist.github.com/charlesreid1/4ce97a5f896ff1c89855a5d038d51535>

-

"NQueens.java". Charles Reid. Github Gist, Github Inc. Edited 20 March 2017. Accessed 20 March 2017. <https://gist.github.com/charlesreid1/7b8d7b9dffb7b3090039849d72c5fff5>

-

"Devel::NYTProf". Adam Kaplan, Tim Bunce. Copyright 2008-2016, Tim Bunce. Published 4 March 2008. Accessed 20 March 2017. <https://web.archive.org/web/20170320081508/http://search.cpan.org/~timb/Devel-NYTProf-6.04/lib/Devel/NYTProf.pm>

-

"Perl/Profiling". Charles Reid. Edited 20 March 2017. Accessed 20 March 2017. <https://web.archive.org/web/20170320081532/https://charlesreid1.com/wiki/Perl/Profiling>

-

"Java/Profiling". Charles Reid. Edited 20 March 2017. Accessed 20 March 2017. <https://web.archive.org/web/20170320081535/https://charlesreid1.com/wiki/Java/Profiling>

-

"JIP - The Java Interactive Profiler." Andrew Wilcox. Published 30 April 2010. Accessed 20 March 2017. <https://web.archive.org/web/20170320081538/http://jiprof.sourceforge.net/>

-

"HPROF". Oracle Corporation. Copyright 1993, 2016. Published 2016. Accessed 20 March 2017. <https://web.archive.org/web/20170320081540/https://docs.oracle.com/javase/7/docs/technotes/samples/hprof.html>