Table of Contents:

Overview of the Undergraduate Research (UGR) Project

South Seattle UGR Project

For the past year, in addition to my duties as a computer science and math instructor at South Seattle College, I have served as a research mentor for an NSF-funded undergraduate research project involving (off-and-on) five different South Seattle students - all of whom have expressed interest in transferring to the University of Washington's computer science program after they finish at South Seattle College.

The students have various levels of preparation - some have taken calculus and finished programming, while others are just starting out and have no programming experience outside of "programming lite" languages like HTML and CSS.

But it's also been an extremely rewarding opportunity. I have gotten the chance to kindle students' interests in the vast world of wireless security, introduced them to essential technologies like Linux, helped them get hands-on experience with NoSQL databases, and guided them through the process of analyzing a large data set to extract meaningful information - baby data scientists taking their first steps.

These are all skills that will help equip students who are bound for university-level computer science programs, giving them both basic research skills (knowing the process to get started answering difficult, complex questions) and essential tools in their toolbelt.

Two students who I mentored as part of a prior UGR project last year (also focused on wireless networks and the use of Raspberry Pi microcomputers) both successfully transferred to the University of Washington's computer science program (one in the spring quarter of 2016, the other in the fall of 2016). Both students told me that one of the first courses they took at the University of Washington was a 2-credit Linux laboratory class, where they learned the basics of Linux. Having already installed Linux virtual machines onto their personal computers, and having used technologies like SSH to remotely connect to other Linux machines, they both happily reported that it was smooth sailing in the course, and it was one less thing to worry about in the process of transferring and adjusting to the much faster pace of university courses.

Engineering Design Project

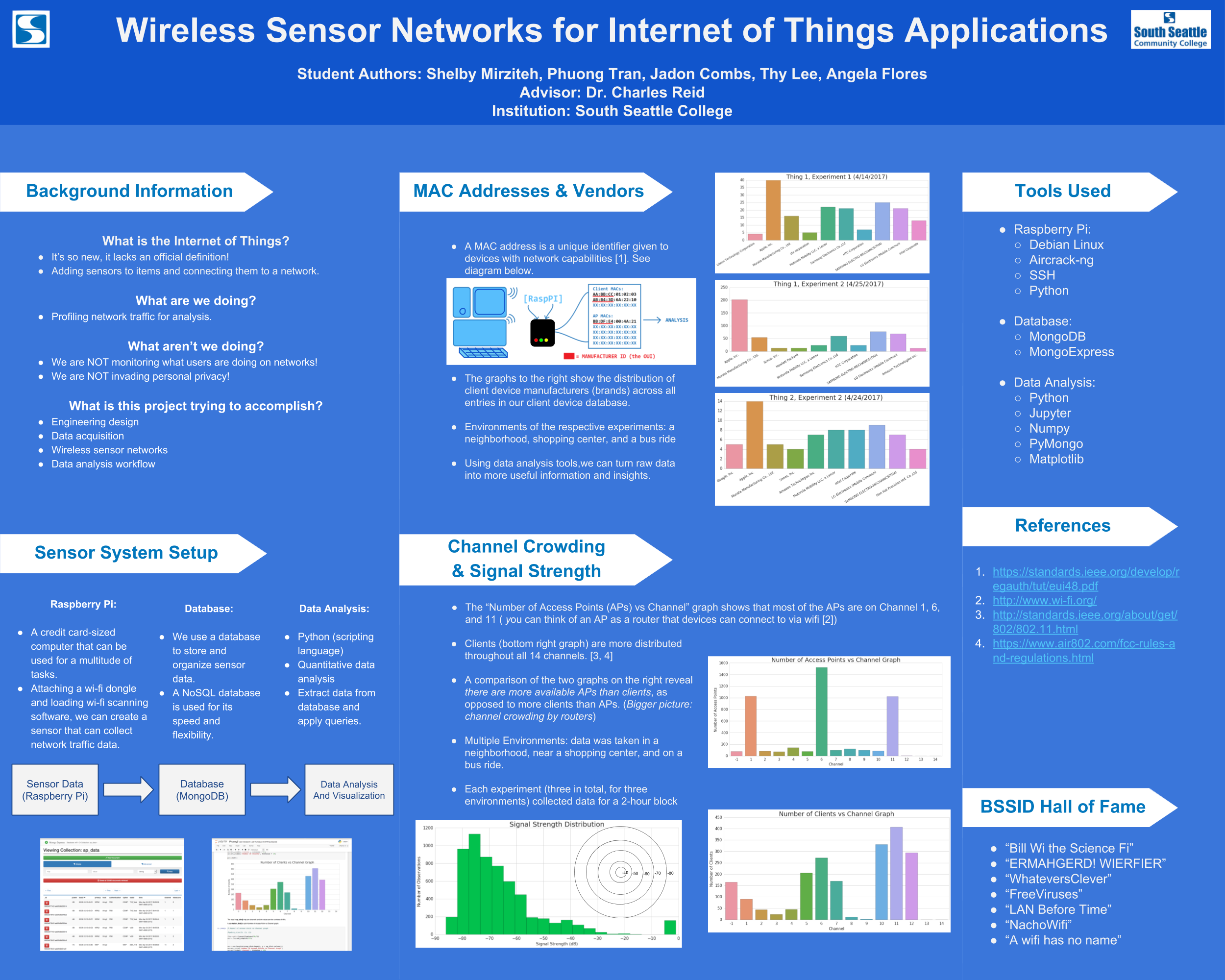

The project was entitled "Wireless Sensor Networks for Internet of Things Applications," and was intended to get students introduced to the basic workflow of any internet of things system: a sensor to collect data, a wireless network to connect sensors together, a warehouse to store data collected from sensors, and a workflow for analyzing the data to extract meaningful information.

The focus was to implement a general workflow using tools that could extend to many internet of things applications, be they commercial, residential, or industrial.

However, the NSF grant provided only a modest amount of funding, intended to go toward stipends to pay students and mentors a modest amount during the quarter, with only modest amounts of money for basic equipment. (We were basically running a research project on a $100 budget.)

That meant the project had to be flexible, scrappy, and run on a shoestring budget. This meant we were limited to cheap, off-the-shelf technologies for the sensors, the sensor platform, and the back-end infrastructure. Two technologies in particular lent themselves nicely to these constraints:

-

Wireless USB antennas - USB wifi dongles are cheap ($10), and the ubiquity of wireless networks and wifi signals meant this would provide us with a rich data set on the cheap.

-

Raspberry Pi - the Raspberry Pi is a credit-card sized microcomputer that runs a full stack Linux operating system. With the low price point ($30) and the many free and open-source tools available for Linux, this was a natural choice for the sensor platform.

The result was a set of wireless sensors - Raspberry Pis with two wireless antennas - one antenna for listening to and collect wireless signal data in monitor mode, and one antenna to connect to nearby wireless networks to establish a connection to a centralized data warehouse server.

Project Components: Extract, Store, and Analyze

The wireless sensor network project had three major components:

-

Extract - using a wireless USB antenna, the Raspberry Pi would listen to wireless signals in the area, creating a profile of local network names, MAC addresses, signal strengths, encryption types, and a list of both clients and routers. Students used the aircrack-ng suite to extract wireless signal information.

-

IMPORTANT SIDE NOTE - students also learned about wiretapping laws and various legal aspects of wireless networks - the difference between monitoring ("sniffing") wireless traffic versus simply building a profile of wireless traffic.

-

Store - students learned about NoSQL databases (we used MongoDB) and set up a NoSQL database to store information about wireless signals. This also required some basic Python programming, as the wireless signal information was exported to a large number of CSV files and had to be programmatically collated and extracted.

-

Analyze - the pinnacle of the project was in the analysis of the wireless signal data that was captured. Students ran several "experiments," collecting wireless signals for 2 hours using a portable battery and a Raspberry Pi with wifi dongles. By running experiments under different conditions (at the college library, at a coffee shop, on a bus), a diverse set of data was gathered, allowing students to extract meaningful information about each experiment from each data set.

The Internet of Things: Not Just a Buzzword

One of the biggest challenges starting out was in getting the students into the right "mindset" about the Internet of Things. This was a challenge that I did not forsee when I came up with the project title. As a chemical engineer working on natural gas processing at a startup company, I knew the value of creating wireless infrastructure to extract data from sensors, throw it into a giant bucket, and utilize computational tools to analyze the data and extract information from it.

But the students involved in the project had no exposure to this kind of workflow. To them, the Internet of Things meant toasters and TVs that were connected to the internet, so they were expecting a design project in which we would make a prototype consumer device intended to connect to the internet.

Further complicating things was the fact that we were focusing on building a data acquisition system - a data analysis pipeline - a workflow for extracting, storing, and analyzing sensor data. We were not focused on the specific types of questions that our specific type of data could answer. This was a bit puzzling for the students (who could not see the intrinsic value of building a data analysis pipeline). Much of their time was spent struggling with what, exactly, we were supposed to be doing with the data, and getting past a contaminated, consumer-centric view of the term "Internet of Things."

It was, therefore, a major breakthrough when one of the students, as we were diving deeper into the data analysis portion, utilizing Python to plot the data, quantitatively analyze it, and better understand it, told me, "Looking back, I realize that I was thinking really narrowly about the whole project. I thought we were going to build a 'smart' device, like a business project. But now I realize our project has a bigger scope, because of the analysis part."

That, in a nutshell, was precisely the intention of the project.

University of Washington Undergraduate Research Symposium

Next week the students present the culmination of their research project at the University of Washington's Undergraduate Research Symposium, where they will have a poster that summarizes their research effort, the results, and the tools that were used.

It is clear to anyone attending the Undergrad Research Symposium that community college students are among the minority of students who are involved in, and benefiting from, research projects. The intention of most of the projects showcased at the symposium is to launch undergraduate students into a graduate level research career and prepare them to hit the ground running, and have a stronger resume and application, when they have finished their undergraduate education and are applying to graduate schools. Many of the research posters at the symposium showcase research using expensive equipment, specialized materials and methods, and complex mathematical methods. Many of the students are mentored by world-class research professors with deep expertise and small armies of graduate and postgraduate researchers.

Despite our research efforts being completely outmatched by many of the undergraduate researchers from the University of Washington (out-funded, out-manned, and out-gunned), our group managed to pull together a very interesting and very ambitious design project that collected a very rich data set. The students were introduced to some useful tools and fields of computer science (wireless networks, privacy and security, embedded devices, databases, Linux), and exposed students to a totally new way of thinking about the "internet of things" that allows them to move beyond the shallow hype of internet-connected toothbrushes. The students have developed the ability to build a data pipeline that could be used by a company to address real, significant problems and needs around data.

All in all, this was an extremely worthwhile, high-impact project that's equipping the next generation of computer scientists with the cognitive tools to anticipate and solve data problems, which (as hardware becomes cheaper and embedded devices become more ubiquitous) are problems that will only become more common in more industries.

The Poster

Here's a rough draft of the poster we will be showing at the UGR symposium: