Table of Contents

The Problem

This is a programming challenge that was assigned to some of my CSE 143 students as a final project for their class.

The origin of this problem was the Association of Computing Machinery (ACM)'s International Collegiate Programming Competition (ICPC), in particular the Pacific Northwest Regional Competition, Division 1 challenges from 2015.

Link to Pacific NW ACM ICPC page.

Problem Description: Checkers

In the Checkers problem, you are presented with a checkerboard consisting of black and white squares. The boards follow a normal checkers layout, that is, all of the pieces occupy only the light or dark squares on the board.

There are several white and black pieces arranged on the checkerboard. Your goal is to answer the following question: can any one single black piece be used to jump and capture all of the white pieces in a single move? This assumes that each of the black pieces are "king" pieces and can jump in either direction.

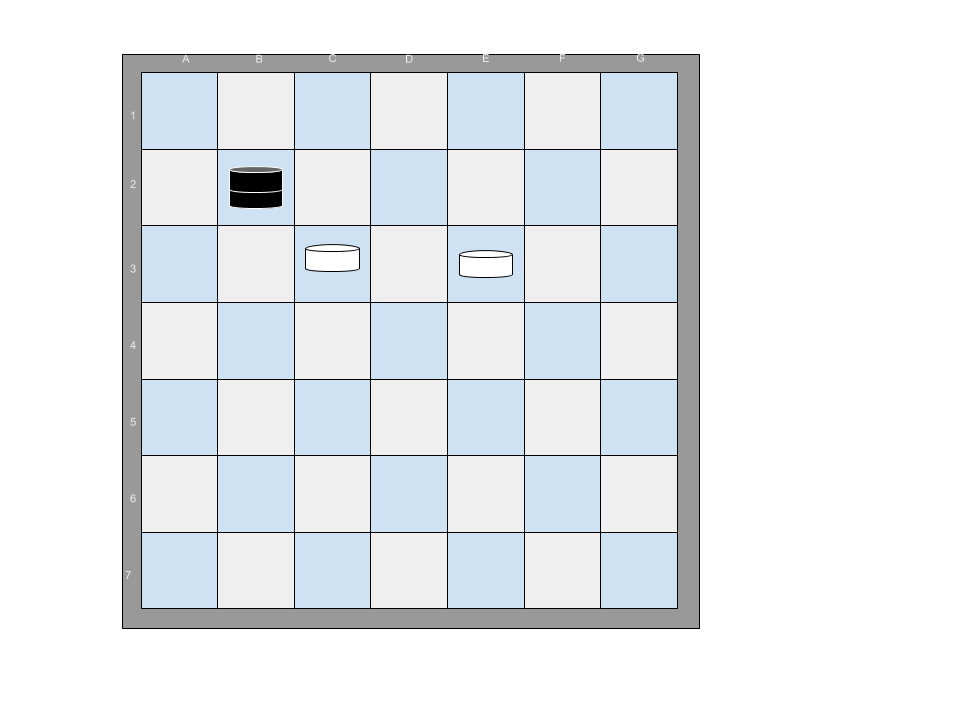

For example, the following 7x7 board configuration has one black piece that can jump all of the white pieces on the board with a single sequence of moves. The black piece at B2 jumps to D4, then to F2.

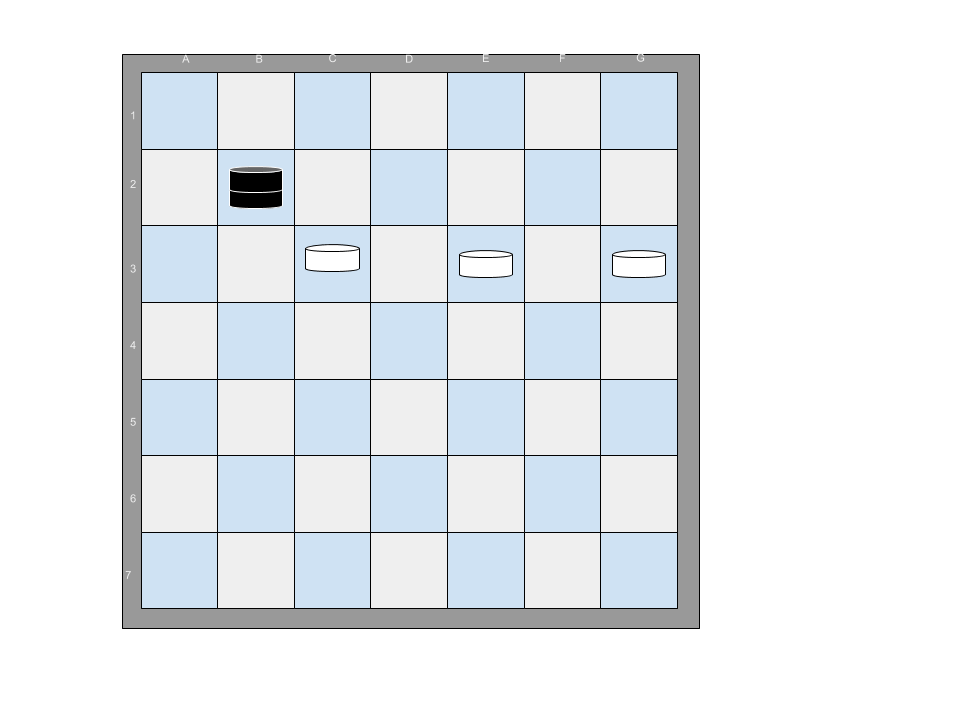

If an additional white piece is added, there is no sequence of moves that will allow any black piece to jump all of the white pieces.

Input File

The input file consists of one line with a single integer, representing the size of the (square) board. Following are characters representing the board state.

. represents a square that pieces cannot occupy - the off-color squares.

_ represents an unoccupied but valid square.

B represents a black piece. W represents a white piece.

Example:

8

._._._._

_._._._.

.W._.B._

_.W.W._.

.W.B._._

_._._._.

.W._.W._

_._._._.

Output

The output is simple: simply state which of the black checkers is capable of jumping each of the white checkers. If none, say "None". If multiple, say "Multiple".

The Solution

Keep It Simple

To successfully solve the checkers problem, it is important to keep it simple. There are different ways of representing the checkers problem abstractly, but the best representation in a program is the simplest one - use a 2D array of chars to represent the board.

Also as usual with permutations of arrangements on boards of fixed size, recursion will be useful here.

Solution Analysis: Parity

We can begin our analysis of the checkers problem with a few observations.

First, we know that the valid squares for checkers are squares that are off by two. But we know further that the black checkers must only move in jumps, which mean that a piece at \((i,j)\) can only reach squares indexed by \((i + 4m, j + 4m)\) or \((i + 4m + 2, j + 4n + 2)\), where \(m, n\) are positive/negative integers.

That is, the checker pieces can make jumps of 2 squares at a time. For example, if a checker starts at the square \((3,3)\) and jumps a white piece down and to the right, it moves to square \((5,5)\) or \((3+2, 3+2)\). If it jumps another white piece up and to the right, it moves to square \((3, 7)\) or \((3, 3 + 4)\).

Further, we know that a black checker can only jump checkers at squares of the form \((a + 2m + 1, b + 2n + 1)\). Thus, black checkers either have the correct parity to jump all of the white checkers, or they have the same parity as the white checkers (in which case they can be ignored).

If a black checker does not have the correct parity to jump white checkers, we can save ourselves time by not checking it.

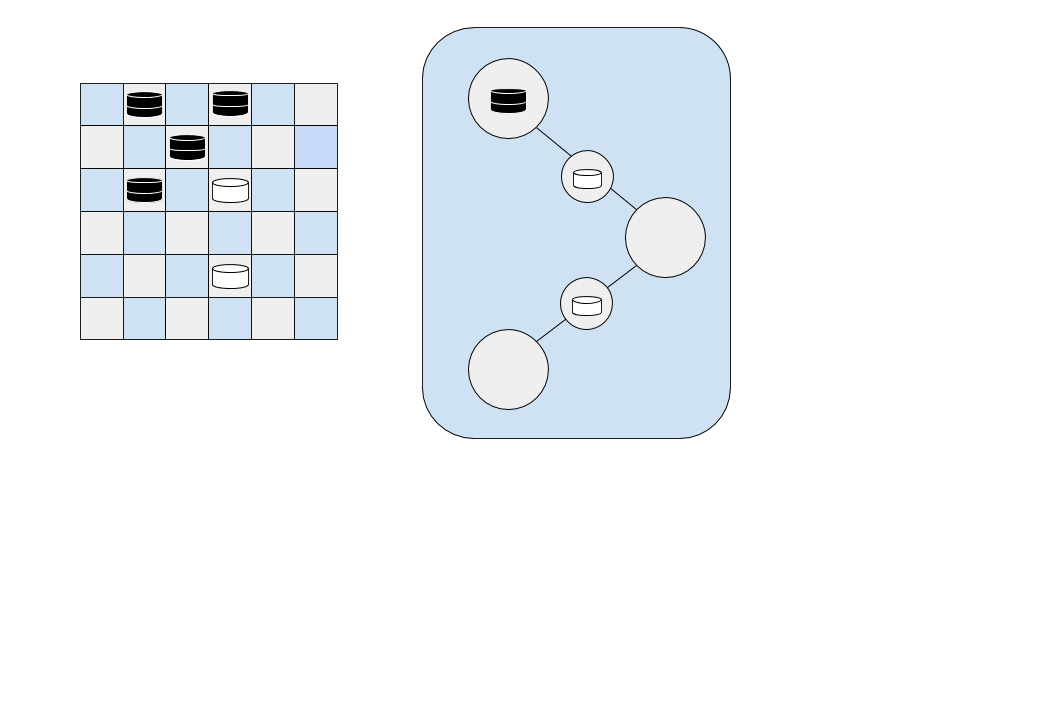

For example, in the checkerboard below, there are four black checkers, but only one (row 2, column 3) has the correct parity to jump each of the white pieces. The other three are

The other three has the correct parity, while the black checker in the right do not.

Solution Analysis: Graphs and Euler Tours

If we examine the squares with correct parity, we can translate the board into a graph representation. Squares with the "jump" parity are nodes on the graph that can perform jumps. (No whites should have jump parity, otherwise the board is impossible.)

Squares with the "jumped" (i.e., white pieces) parity are nodes that are being jumped. These nodes form the edges between jump parity nodes, and these edges must be occupied by a white piece for a black piece to be able to pass through them. In this way, we can think of white pieces as "bridges" between jump parity squares.

This representation leads to thinking about the tour the black checker takes through the checkerboard as an Euler tour across the graph.

An Euler Tour, made famous by the Seven Bridges of Königsberg problem solved by Euler in 1736, is a path that visits each node of the graph, traversing each edge once and only once.

Euler showed that an Euler path visiting each edge of the graph depends on the degree of each node in the graph. For an Euler path to exist, the graph must be connected and there must be exactly zero or two nodes of odd degree.

If we walk through the checker board and construct the graph (or assemble the information that the graph would have told us), we can determine whether an Euler tour exists, and find the Euler tour.

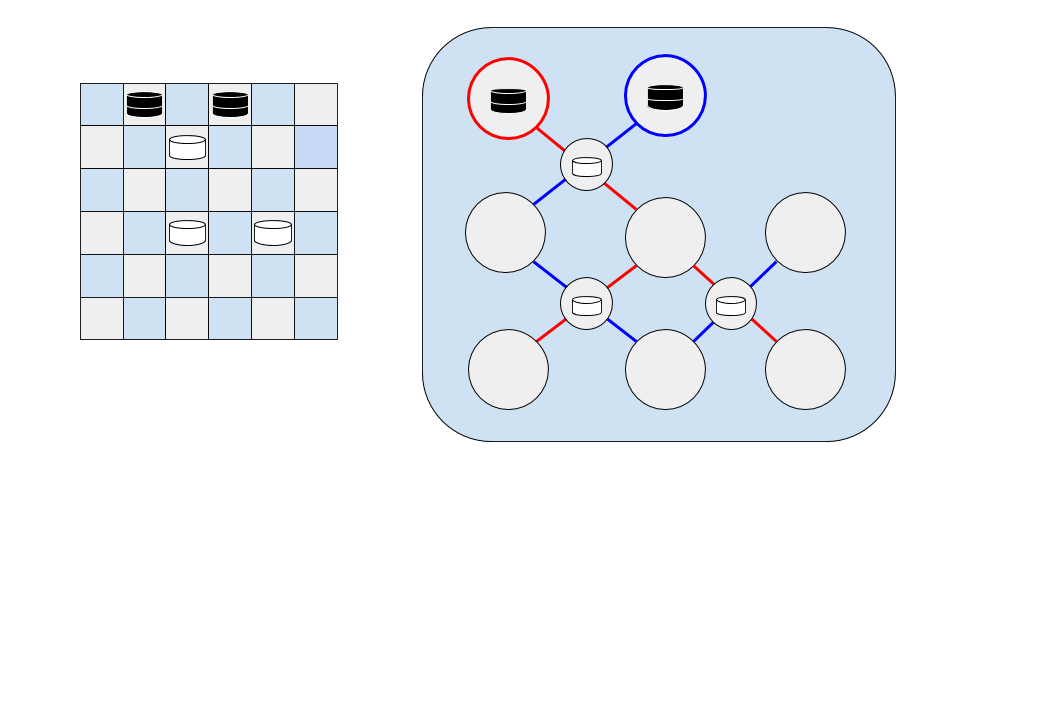

The example above shows a checkerboard with two white pieces forming two edges. The first white piece connects a jump parity square with a black piece on it to a jump parity square that is empty. The second white piece connects two empty jump parity squares.

The black "entrance" node has an odd degree (1). The second, unoccupied node has an even degree (2). The third, unoccupied node has an odd degree (1). Therefore the graph has two nodes of odd degree, so an Euler tour exists.

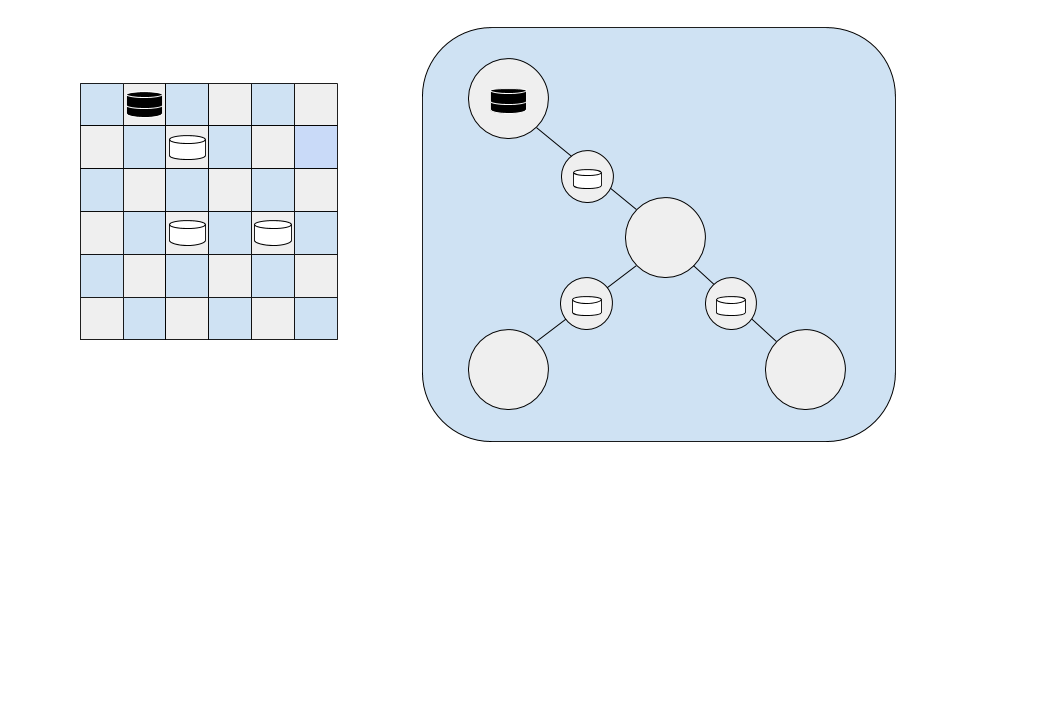

If we modify this example to add one additional white checker piece on a square with correct parity, the Euler Path analysis identifies this as a board with no solution:

This is because three of the nodes have degree 1 and one node has degree 3, for a total of 4 nodes with odd degree. The requirements for an Euler Tour to exist (equivalent to saying a solution to the Checkers problem can be found for a given black checker) are violated, so no solution can be found.

If we were to add a second black checker piece two squares away, an alternate graph (highlighted in blue) can be constructed, and an alternate Euler path through the graph is available.

On the red graph, each node has an odd degree, so the number of nodes with odd degree is not 0 or 2. On the blue graph, only the start and end nodes have an odd degree (1), while the rest of the nodes have a degree of 2 (one input and one output). This means an Euler Tour exists on the blue graph.

In practice, a given black piece has a given graph connecting squares on the checkerboard - we can ask each node on that graph for its degree, and the degree of its neighbors, and if a black piece results in an invalid number of odd nodes, we can abandon it.

Solution Algorithm

The algorithm to find solutions to this problem very roughly follows this pattern: * First, perform a parity check to determine if a solution is impossible. * Loop over each square of the board, looking for black pieces * For each black piece: * Look at each neighbor: * Determine if there is a square to jump to if neighbor is white * Determine number of odd neighbors * Fail if more than 2 odd neighbors, or 2 odd neighbors and odd self * Backtracking: explore neighbors, determine if all whites can be jumped

Solution Pseudocode

The solution code has three basic parts (four, including the input parser): * Initialize and parse the board * Loop over each square, checking if black piece is a solution * Function to check if black piece is a solution piece * (Recursive backtracking) function to jump each white piece possible to jump.

Start with the initialization of the board and looping over each black piece to check if it is a solution piece:

initialize solutions counter

initialize board

for each s in squares:

if s is black piece:

if s is solution piece:

increment solutions counter

save location

print summary

Now we just need to implement functions that can (a) check if a square contains a black piece (easy) and (b) check if a black piece is a solution piece (uh... kind of what the whole problem boils down to, no?)

We break that functionality into a separate function. Here is the pseudocode to check if a black piece in a particular square is a solution piece. This function iterates over squares with jump parity - that means this function traverses the nodes only in the graph representation of the checkerboard.

This function enforces the requirement that no node can have more than 2 odd neighbors, or be odd if it has more than 2 odd neighbors, since a graph must have 0 or 2 nodes with odd degree in the graph for an Euler Tour to exist.

While we're at it, we also check if there are any white checker pieces without a square to land in when they are jumped (i.e., landing square blocked by another black piece or at edge of board).

function is solution piece:

for each square of similar "jump" parity:

for each neighbor:

check if neighbor is odd

if a neighbor square is white:

if next square is not empty:

fail fast

if more than 2 odd neighbors, or 2 neighbors and odd:

fail fast

# we have a viable solution

recursively count number of jumped white checkers

if number of jumped white checkers equals number of white checkers on board:

return true

Finding squares of similar jump parity is as easy as looping over each row and column, and checking if it is off by 2 with the row/column of the black checker piece that we are currently checking. Checking if a neighbor is odd is as straightforward as counting its degree - checking each of its four neighbors and determining which ones are open. This leaves finding the number of jumped white checkers as the only functionality left to define.

define number of jumped white checkers:

initialize white checkers jumped counter

for each neighbor:

if white piece, unvisited, with an empty place to jump to:

visit white piece

increment white checkers jumped

call number of jumped white checkers on next next neighbor

# this should be the empty space

return number white checkers jumped

References

- "ACM Pacific Region Programming Competition." Association of Computing Machinery. 19 June 2017. <http://acmicpc-pacnw.org/>