This is the first of several posts that will walk through an implementation of the Enigma cipher in code.

Thanks to the website of the late Tony Sale for providing a wealth of detailed, accurate information entirely free of graduate level mathematics, and includes some very clear examples for luddites like me who need everything spelled out really clearly.

There is also a Wikipedia article offering detailed information about the mathematical cryptanalysis of the Enigma, and covering some of the strengths and weaknesses of the machine: Cryptanalysis of the Enigma.

Background

The Enigma machine was a device used by the German military to encrypt communications during World War II. The machine was essentially a large electronic circuit implementing a black-box encrypt/decrypt function. By design, the circuitry of the machine could be used for both encryption and decryption.

The Enigma played an important role in the development of the first electronic computer. Alan Turing led a team at Bletchley Park, in England, that constructed machines that could crack the Enigma code. This led to the development of the conceptual Turing machine and the creation of the first electronic computers. By narrowing the space of possible keys using Enigma's weaknesses, these electronic computers could be used to explore the remaining key space.

There were several variations of the Enigma. Each operated on the same basic principle: the operator entered a letter, which was transformed into a signal. That signal was passed through several components of the Enigma machine, and underwent a series of linear transformations until its ciphertext was output. The encrypted output character would light up on a second keyboard, and the operator could transcribe the message.

Black Box Representation

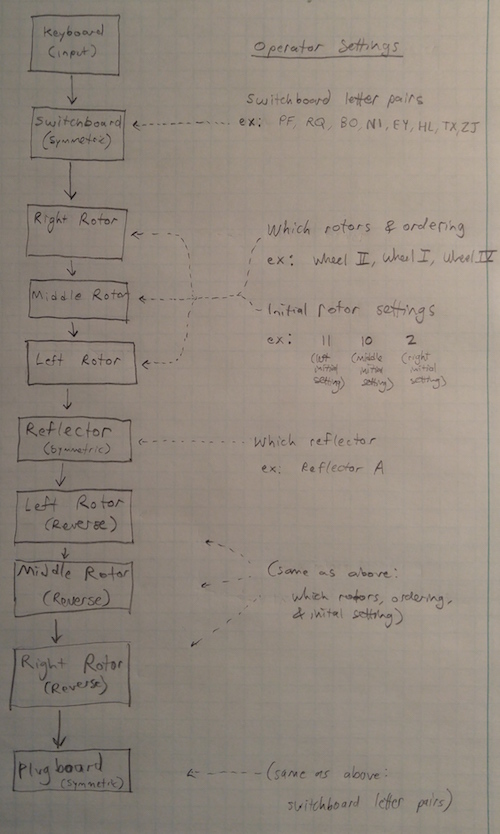

The following diagram lays out the Enigma circuitry using black boxes. The signal starts at the keyboard, where the operator types a letter. That letter is transformed into an electrical signal, which is sent through a series of components. First is the switchboard in the front, which swaps a few letter pairs. Next, the signal passes through three rotor wheels, each of which scrambles the alphabet. The signal is then passed into a reflector, which swaps every character with some other character. The reflector made the Enigma a symmetric machine. The signal was sent out of the reflector and passed through each rotor in reverse order. Finally, the signal passed through the switchboard at the front, and the resulting letter lit up, allowing the operator to transcribe the message.

Components

There were three principal components of the machine: a switchboard, a set of rotor wheels, and a reflector.

Switchboard

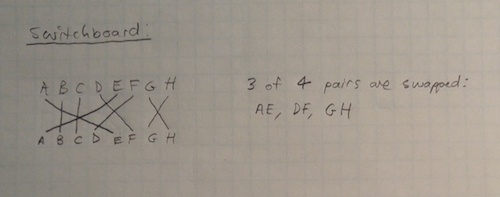

When the operator entered a key on the input keyboard, the key pressed was transformed into a signal. On the front of the Enigma machine was a set of plugs, one for each letter. Operators would connect pairs of letters using plugs, which would swap letters. If an operator connected the A and K ports, and typed "A" on the keyboard, the signal representing "A" would travel to the switchboard, where it would be transformed into the signal representing "K".

Typically the Enigma operators would only connect 7-10 pairs of letters, with the remaining 6-12 letters untransformed by the switchboard. The switchboard led to a huge number of possible encryption schemes, and was the single component that made the Enigma diffficult to crack. Commercial versions of the Enigma, without the plugboard, were sold to banks and other entities in Germany, but without the plugboard, the key space was reduced dramatically, making these codes "easy" to crack.

The image above illustrates how a switchboard would work for a simple 8-symbol alphabet "ABCDEFGH". Only 3 of 4 pairings are made in this example.

Rotor Wheels

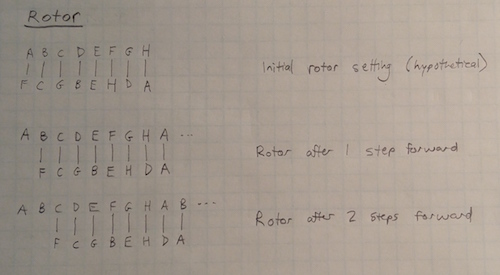

The rotor wheels were a set of interchangeable wheels that would perform a substitution cipher. Each wheel corresponded to a particular alphabet in scrambled order (these rotors were not performing simple shift Caesar ciphers). Based on the order of the wheels, the signal, representing the letter the operator typed on the keyboard, that came out of the switchboard would undergo three alphabet scrambles (also called affine ciphers).

Because the wheels rotated with each keypress, the actual Affine cipher used by each wheel changed at each step.

To complicate the way the rotors turned, the designer of the Enigma added clasps and notches to each rotor at different letters. When the notch of one rotor and the clasp of the rotor to the left matched, they would turn together. The right-most wheel rotated once each key press, the center wheel rotated once every 26 key presses, and the left wheel rotated once every 676 key presses. Although these rates remained the same due to the number of notches, the exact locations of the notches dictated the timing of the rotations. The ordering of the wheels and their initial settings were therefore important to how the message was encrypted or decrypted.

The German military distributed code books that contained daily settings for the Enigma machines, so that all Enigma operators had the same settings. These code books specified which wheels to load into the Enigma (three out of five possible rotors I II III IV and V), as well as the initial rotation to apply to each.

The image above shows how the rotor would work for the 8-character alphabet "ABCDEFGH". The wheel has a set arrangement of scrambled letters, but the scramble shifts each time the rotor is advanced. This allows 1 wheel to provide as many different scrambles as there are symbols in the alphabet.

Reflector

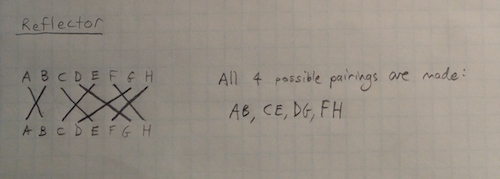

Having passed through the three rotor wheels, each scrambling the original character signal input by the operator into the keyboard, the signal then entered the reflector. It did precisely what the name suggests - it reflected a signal back through the machine. Its design was very similar to the switchboard in the front of the machine, except it created 13 pairs of letters, so that every letter was paired with some other letter. The reflector, like the rotor wheels, was removable and could be selected from a set.

The reflector is a curious part of the Enigma design, because it represents an attempt at convenience, which led to a gaping security flaw that Bletchley Park was able to exploit. The nature of the reflector is that it is symmetric: it pairs each letter with some other letter, and the pairings are mutual. If the reflector turns every "P" into "H", it also turns every "H" into "P". This symmetry gives the Enigma the property that you no longer need an "encrypt" or "decrypt" mode: if you take a plaintext message and run it through the Enigma machine once, you'll get the cipher text back. If you run it through the Enigma machine twice, you'll get the same plaintext back. This obviated the need for a switch on the Enigma, to go between "encrypt" and "decrypt" modes.

However, this property also means that no letter can ever be encoded as itself - a property called derangement. While the switch board at the front and the rotor wheel scrambles would sometimes encode a letter as itself (for example, Rotor I encodes "S" as "S", Rotor II encodes "A" as "A" and "Q" as "Q", and Rotor III encodes "N" as "N"), the reflector would never do so. Thus, despite an astronomical number of possible settings, and complicated machinery and circuitry, no matter what the Enigma's settings, no letter would ever be encoded as itself. This property can be exploited to rule out the location of certain words or phrases at certain locations in the message, which is precisely how Bletchley Park attacked the Enigma cipher.

The image above illustrates a reflector for the 8-symbol alphabet "ABCDEFGH". Each of the 4 possible pairings are made, so no letter will be encoded to itself by the reflector.

Had the middle rotor wheels remained stationary, multiple wheels would have been redundant - any arbitrary sequence of alphabet scrambles can be collapsed into a single scramble. However, the wheels were designed to rotate at various rates. Each time the wheels rotated, it changed the scramble provided by the wheel that had rotated.

This means the Enigma worked by using a totally different scramble for each character in a message, with the scrambles constantly changing, each character, over and over. Because the number of possible scrambles with a 26 character alphabet is \(26! = 403,291,461,126,605,635,584,000,000\), which is a trillion trillions.

The Enigma and Random Number Generators

By using a mechanical device with the same construction and the same common initial settings, operators were able to generate random keys from an astronomical range of permutations, but in a mechanically reproducible way.

This makes Enigmas much like a random number generator, with the initial settings being the seed. If there are 32 or 64 bits used to store a number, that's 32 or 64 bits of randomness. Large numbers of combinations indeed.

Sources

-

"The Enigma Cipher". Tony Sale and Andrew Hodges. Publication date unknown. Accessed 18 March 2017. <https://web.archive.org/web/20170320081639/http://www.codesandciphers.org.uk/enigma/index.htm>

-

Copeland, B.J. "Alan Turing". Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc. Published 23 February 2016. Accessed 18 March 2017.

-

"Cryptanalysis of the Enigma". Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. Edited 11 January 2017. Accessed 18 March 2017. <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cryptanalysis_of_the_Enigma>