Table of Contents

Background: Traveling Salesperson Problem (TSP)

The traveling salesperson problem, or TSP, is a classic programming problem and an important one in computer science,

and applications in operations research and optimization.

The idea is that you have a set of \(N\) cities, connected by various roads, each with their own distances.

That is, we have a set of \(E\) roads, each with their own distance \(d_j, j=1 \dots E\).

The question is, what is the shortest path that a salesperson can take to visit all \(N\) cities, traveling the shortest possible total distance

and visiting each city once and only once?

Like the N queens problem, the traveling salesperson problem is a good candidate for recursive backtracking.

Also like the N queens problem, there are certain shortcuts we can take to trim down the possibilities we explore.

Computer science pages on Wikipedia are generally pretty high in quality, and the traveling salesman problem

page is no exception. It give a very thorough overview of the important aspects of the problem.

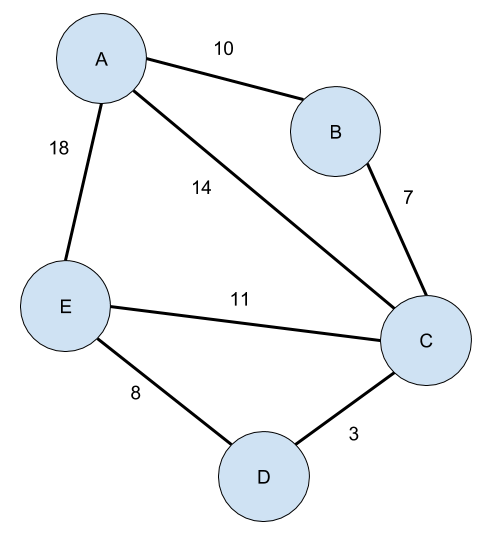

Graphs

Graphs are mathematical objects first utilized by Leonhard Euler to solve the

Seven Bridges of Köningsberg problem.

The concept is simple: you have a bunch of dots connected with lines.

The dots are called nodes, and the lines are called edges.

Graphs can be directed, meaning the edges are like arrows with particular directions, or undirected,

meaning the edges simply represent a connection between the two nodes.

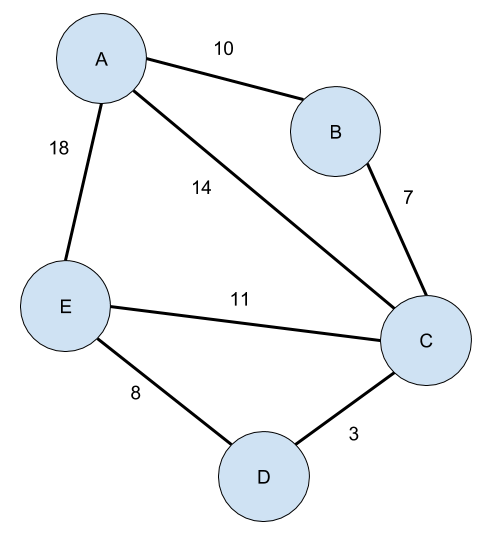

Here is an example of a graph with five nodes, with each edge labeled with its distance:

We will skip over a vast amount of detail about graph theory that is both fascinating and useful,

but M. E. J. Newman's paper "The structure and function of complex networks"

(self-published and written as a course review) is an extremely detailed

and academically rigorous overview of just about every important detail of the field.

Number of Edges

The maximum number of roads or edges \(E\) depends on the number of nodes as \(E = \dfrac{N(N-1)}{2}\), which is derived from

the formula for 2 choose N (because edges connect 2 nodes). For k choose N, the formula is given by:

$$

C_{N,k} = \dfrac{N!}{k! (N-k)!}

$$

and for 2 choose N, it is given by:

$$

C_{N,2} = \dfrac{N(N-1)}{2}

$$

This is the maximum number of undirected edges in a graph.

If the graph is directed, then order matters (the edgge A->B is no longer the same as B->A),

so we have to use the formula for k pick N,

$$

P_{N,k} = \dfrac{N!}{(N-k)!}

$$

which results in

$$

P_{N,2} = N (N-1)

$$

possible edges.

Number of Solutions

Naturally, the question of the total solution space arises.

Assuming the graph of cities is perfectly connected (representing an upper limit on problem complexity),

how does the number of solutions change as the number of nodes increases?

We can start with a trivial graph, and count the number of possible paths

through the entire graph, starting with a specific node.

This is equivalent to counting permutations of a string that start with a specific character.

ABCDE

ABCED

ABDCE

ABDEC

ABECD

ABEDC

For a string of length \(N\), the string has \((N-1)!\) possible permutations that start with a specific character.

Therefore, as the number of nodes \(N\) increases, the number of possible solutions increases as \((N-1)!\),

making the complexity class of the problem \(O(N!)\).

Solution: Recursive Backtracking

Here is pseudocode for a recursive backtracking method:

explore(neighbors):

if(no more unvisited neighbors):

# This is the base case.

if total distance is less than current minimum:

save path and new minimum

else:

# This is the recursive case.

for neighbor in unvisited neighbors:

visit neighbor

explore(new_neighbors)

unvisit neighbor

Care is needed to prevent infinite loops in which the traveling salesperson goes back and forth between two cities.

As we traverse the graph, we can mark each node as visited, to ensure we don't revisit nodes and go in circles.

Nodes can be implemented as a Node object in Java, with each Node having a few characteristics:

- String label

- Container of Node pointers pointing to neighbors

- Boolean flag: have we visited this node already?

Likewise, the graph edges can be represented using integers or doubles.

Solving the TSP with Java and Guava

Google Guava is a library of high-performance data containers in Java.

The library provides some useful graph objects that we can use to easily solve the TSP on a graph.

Basics of Guava

Install and use Guava by visiting the Guava project on Github,

find the page for their latest release (here is version 21.0),

and getting the latest .jar file.

To compile with the jar file, you can either utilize an IDE like Eclipse or IntelliJ,

or you can compile from the command line, specifying the class path using the -cp flag:

$ javac -cp '.:/path/to/guava/jars/guava-21.0.jar' TSP.java

$ java -cp '.:/path/to/guava/jars/guava-21.0.jar' TSP

More information can be found on the charlesreid1.com wiki: Guava

Guava Graphs

Graph objects in Guava are implemented using a set of objects: Graphs, ValueGraphs, and Networks.

Graph objects treat edges as very simple and assumes they contain no information and simply link nodes.

ValueGraphs associate a single non-unique value with each edge on the graph. This can also be used to solve the TSP.

Network objects treat nodes and edges both as objects, and has the ability to deal with more complex edges: model multi-edges, repeated edges, directed edges, etc.

We will use a Network object and design our own graph Node and Edge objects.

Link to Guava wiki on how to build graph instances

Guava API Documentation: Network

Guava API Documentation: Graph

Guava API Documentation: ValueGraph

Guava Mutable vs Immutable

Guava makes a distinction between mutable graphs, which can be modified, and immutable graphs, which cannot.

Immutability provides some safety and assurances to programmers, and can make things faster.

When we construct the network, we need a mutable graph to modify (add nodes and edges).

But once the network is constructed, it is finished: we don't need to modify the network while we're solving the problem.

Therefore, we construct a mutable network, assemble the graph for the given problem, and copy it into an immutable graph.

We then use the immutable graph to access the graph while solving.

Importing Guava

Starting with import statements, we'll use a couple of objects from the Java API, and from Google's Guava library:

import java.util.Set;

import java.util.Map;

import java.util.TreeMap;

import java.util.Arrays;

import com.google.common.graph.Network;

import com.google.common.graph.NetworkBuilder;

import com.google.common.graph.ImmutableNetwork;

import com.google.common.graph.MutableNetwork;

For more info on why we don't just do the lazier

import java.util.*;

import com.google.common.graph.*;

see Google's Java style guide.

TSP Class

Let's lay out the TSP class definition. This class is simple, and wraps a few pieces of data:

the current route, the current distance, and the minimum distance.

Note that we could also save the solution in a container, instead of printing it,

by defining a static class to hold solutions, but we'll keep it simple.

/** This class solves the traveling salesman problem on a graph. */

class TSP {

// The actual graph of cities

ImmutableNetwork<Node,Edge> graph;

int graphSize;

// Storage variables used when searching for a solution

String[] route; // store the route

double this_distance; // store the total distance

double min_distance; // store the shortest path found so far

/** Defaut constructor generates the graph and initializes storage variables */

public TSP() {

// TODO

}

/** This method actually constructs the graph. */

public ImmutableNetwork<Node,Edge> buildGraph() {

// TODO

}

/** Public solve method will call the recursive backtracking method to search for solutions on the graph */

public void solve() {

// TODO

}

/** Recursive backtracking method: explore possible solutions starting at this node, having made nchoices */

public void explore(Node node, int nchoices) {

// TODO

}

/** Print out solution */

public void printSolution() {

// TODO

}

/** Print out failed path */

public void printFailure() {

// TODO

}

Node Class (Cities)

Now we can define the Node class to represent cities on the graph.

class Node {

public String label;

public boolean visited; // Helps us to keep track of where we've been on the graph

public Node(String name){

this.label = name;

this.visited = false;

}

public void visit(){

this.visited = true;

}

public void unvisit() {

this.visited = false;

}

}

Like a lined list node, we want to keep graph nodes simple.

Note that Nodes don't need to store information about their neighbors.

That's what we'll use Google Guava for!

Edge Class (Roads)

Edge classes are even simpler, wrapping a single integer:

class Edge {

public int value;

public String left, right; // For convenience in construction process. Not necessary.

public Edge(String left, String right, int value) {

this.left = left;

this.right = right;

this.value = value;

}

}

Note that left and right are used for convenience only during the graph construction process.

Like the nodes, the edges don't need to know who their neighbors are,

since that's what the Google Guava graph object will take care of.

TSP Constructor and Building the Graph

Constructor

The TSP class constructor should do a few things:

- Construct a graph, with a given set of cities and distances.

- Initialize arrays and cumulative variables that will be used by the backtracking method.

The actual graph construction process is put into another function called buildGraph(),

so really the constructor just calls a function and then does #2.

/** Defaut constructor generates the graph and initializes storage variables */

public TSP() {

// Build the graph

this.graph = buildGraph();

this.graphSize = this.graph.nodes().size();

// Initialize route variable, shared across recursive method instances

this.route = new String[this.graphSize];

// Initialize distance variable, shared across recursive method instances

this.this_distance = 0.0;

this.min_distance = -1.0; // negative min means uninitialized

}

Build Graph Method

Now we actually use Guava's Immutable Network object,

which takes two templated types, T1 and T2,

which correspond to the node types and the edge types.

We use a NetworkBuilder object to build the Network

(an example of the factory template).

This returns a MutableNetwork of Node and Edge objects,

which we can then connect up using some built-in methods.

Here are some built-in methods available for a MutableNetwork:

addEdge(node1, node2, edge)

addNode(node1)

removeEdge(edge)

removeNode(node)

Now here is the construction of the graph, using the Google Guava library.

There are two loops here: one for cities, and one for edges.

In the loop over each city,we create a new node and add it to the graph.

To be able to easily retrieve the Nodes we have created,

we also store references to the nodes in a map called all_nodes.

When we construct edges, we use the map of all nodes all_nodes to get references to the Node objects

that correspond to a label. That way, if an edge connects "A" with "B" at a distance of 24,

we can turn "A" and "B" into references to the Node objects A and B.

/** This method actually constructs the graph. */

public ImmutableNetwork<Node,Edge> buildGraph() {

// MutableNetwork is an interface requiring a type for nodes and a type for edges

MutableNetwork<Node,Edge> roads = NetworkBuilder.undirected().build();

// Construct Nodes for cities,

// and add them to a map

String[] cities = {"A","B","C","D","E"};

Map<String,Node> all_nodes = new TreeMap<String,Node>();

for(int i = 0; i<cities.length; i++) {

// Add nodes to map

Node node = new Node(cities[i]);

all_nodes.put(cities[i], node);

// Add nodes to network

roads.addNode(node);

}

// Construct Edges for roads,

// and add them to a map

String[] distances = {"A:B:24","A:C:5","A:D:20","A:E:18","B:C:10","B:D:20","C:D:4","C:E:28","D:E:3"};

Map<String,Edge> all_edges = new TreeMap<String,Edge>();

for(int j = 0; j<distances.length; j++) {

// Parse out (city1):(city2):(distance)

String[] splitresult = distances[j].split(":");

String left = splitresult[0];

String right = splitresult[1];

String label = left + ":" + right;

int value = Integer.parseInt(splitresult[2]);

// Add edges to map

Edge edge = new Edge(left, right, value);

all_edges.put(label, edge);

// Add edges to network

roads.addEdge(all_nodes.get(edge.left), all_nodes.get(edge.right), edge);

}

// Freeze the network

ImmutableNetwork<Node,Edge> frozen_roads = ImmutableNetwork.copyOf(roads);

return frozen_roads;

}

Solving and Exploring with Recursive Backtracking

Solve Method

The structure of some recursive backtracking problems is to create a public and a private interface,

with the public interface taking no parameters or a single parameter that the user will know,

and the private method taking a parameter specific to the implementation. That's the pattern we use here.

The solve method sets up the problem by picking a starting node (in this case, an arbitrary starting node).

It then gets a reference to that node on the graph, and calls the recursive explore() method,

which begins the recursive backtracking method.

/** Public solve method will call the recursive backtracking method to search for solutions on the graph */

public void solve() {

/** To solve the traveling salesman problem:

* Set up the graph, choose a starting node, then call the recursive backtracking method and pass it the starting node.

*/

// We need to pass a starting node to recursive backtracking method

Node startNode = null;

// Grab a node, any node...

for( Node n : graph.nodes() ) {

startNode = n;

break;

}

// Visit the first node

startNode.visit();

// Add first node to the route

this.route[0] = startNode.label;

// Pass the number of choices made

int nchoices = 1;

// Recursive backtracking

explore(startNode, nchoices);

}

Explore (Backtrack) Method

And now, on to the recursive backtracking method.

The method takes as a parameter which node we are currently on and the number of cities we have visited.

As multiple explore methods choose different paths, they pass references to different node objects in the graph,

and they pass different values of nchoices.

The methods, when they do not encounter a solution, will choose a next node and call the explore method on it.

Each instance of the explore method marks nodes as visited or unvisited on the same shared graph object.

This allows instances of the function to share information about their choices with other instances of the function.

All recursive methods must consist of a base case and a recursive case:

Base case:

- We've visited as many cities as are on the graph.

- Check if this is a new solution (distance less than the current minimum).

Recursive case:

- Make a choice (mark node as visited, add city to route).

- Explore the consequences (recursive call).

- Unmake the choice (mark node as unvisited, remove city from route).

- Move on to next choice.

/** Recursive backtracking method: explore possible solutions starting at this node, having made nchoices */

public void explore(Node node, int nchoices) {

/**

* Solution strategy: recursive backtracking.

*/

if(nchoices == graphSize) {

//

// BASE CASE

//

if(this.this_distance < this.min_distance || this.min_distance < 0) {

// if this_distance < min_distance, this is our new minimum distance

// if min_distance < 0, this is our first minimium distance

this.min_distance = this.this_distance;

printSolution();

} else {

printFailure();

}

} else {

//

// RECURSIVE CASE

//

Set<Node> neighbors = graph.adjacentNodes(node);

for(Node neighbor : neighbors) {

if(neighbor.visited == false) {

int distance_btwn;

for( Edge edge : graph.edgesConnecting(node, neighbor) ) {

distance_btwn = edge.value;

}

// Make a choice

this.route[nchoices] = neighbor.label;

neighbor.visit();

this.this_distance += distance_btwn;

// Explore the consequences

explore(neighbor,nchoices+1);

// Unmake the choice

this.route[nchoices] = null;

neighbor.unvisit();

this.this_distance -= distance_btwn;

}

// Move on to the next choice (continue loop)

}

} // End base/recursive case

}

Main and Utility Methods

Last but not least, add the method that actually calls the TSP object's solve method,

and define what to do when we encounter a new solution.

This program just prints out new solutions as they are found,

but you could also add them to a map (map routes to distances),

or quietly keep track of the shortest path and not print it until the end.

class TSP {

public static void main(String[] args) {

TSP t = new TSP();

t.solve();

}

...

Additionally, we may want to perform a certain action when we find a new minimum distance.

Note that this method may be called multiple times during the solution procedure.

/** Print out solution */

public void printSolution() {

System.out.print("@@@@@@@@@@\tNEW SOLUTION\t");

System.out.println("Route: "+Arrays.toString(this.route)

+"\tDistance: "+this.min_distance);

}

/** Do nothing with failed path */

public void printFailure() {

// Nope

}

Program Output

Initial Graph Structure and Solution

In the construction of the graph, we defined our graph as:

String[] distances = {"A:B:24","A:C:5","A:D:20","A:E:18","B:C:10","B:D:20","C:D:4","C:E:28","D:E:3"};

This is the graph that we're solving the TSP problem on.

Here are the results when the program is compiled and run:

$ javac -cp '.:/Users/charles/codes/guava/jars/guava-21.0.jar' TSP.java

$ java -cp '.:/Users/charles/codes/guava/jars/guava-21.0.jar' TSP

@@@@@@@@@@ NEW SOLUTION Route: [A, B, C, D, E] Distance: 41.0

@@@@@@@@@@ NEW SOLUTION Route: [A, C, B, D, E] Distance: 38.0

@@@@@@@@@@ NEW SOLUTION Route: [A, E, D, C, B] Distance: 35.0

The answers given were satisfactory and correct, so we moved on to

a more advanced graph construction process that utilized a static class

to generate random, fully-connected graphs. This also implemented

additional functionality to export to Dot format. This static RandomGraph

class will be covered in later post.

Here is the resulting output of the random graph generator for a 6-node TSP problem,

with the sequence of shortest routes found by the algorithm:

java -cp '.:/Users/charles/codes/guava/jars/guava-21.0.jar' TSP 6

------------------- TSP ----------------------

!!!!!YAY!!!!!! NEW SOLUTION Route: [0, 1, 3, 2, 4, 5] Distance: 291.0

!!!!!YAY!!!!!! NEW SOLUTION Route: [0, 1, 3, 5, 4, 2] Distance: 249.0

!!!!!YAY!!!!!! NEW SOLUTION Route: [0, 1, 2, 4, 3, 5] Distance: 246.0

!!!!!YAY!!!!!! NEW SOLUTION Route: [0, 1, 5, 3, 4, 2] Distance: 203.0

!!!!!YAY!!!!!! NEW SOLUTION Route: [0, 3, 5, 1, 4, 2] Distance: 178.0

!!!!!YAY!!!!!! NEW SOLUTION Route: [0, 2, 4, 1, 5, 3] Distance: 163.0

Done.

And for 12 nodes, a problem twice that size, here is the graph and corresponding output:

and the output:

java -cp '.:/Users/charles/codes/guava/jars/guava-21.0.jar' TSP 12

------------------- TSP Version 2: The Pessimistic Algorithm ----------------------

!!!!!YAY!!!!!! NEW SOLUTION Route: [0, 1, 7, 4, 2, 9, 10, 5, 3, 6, 8, 11] Distance: 585.0

!!!!!YAY!!!!!! NEW SOLUTION Route: [0, 1, 7, 4, 2, 9, 10, 5, 3, 8, 11, 6] Distance: 558.0

!!!!!YAY!!!!!! NEW SOLUTION Route: [0, 1, 7, 4, 2, 9, 10, 5, 3, 8, 6, 11] Distance: 522.0

!!!!!YAY!!!!!! NEW SOLUTION Route: [0, 1, 7, 4, 2, 9, 10, 6, 5, 3, 8, 11] Distance: 499.0

!!!!!YAY!!!!!! NEW SOLUTION Route: [0, 1, 7, 4, 2, 9, 10, 11, 8, 6, 5, 3] Distance: 460.0

!!!!!YAY!!!!!! NEW SOLUTION Route: [0, 1, 7, 4, 2, 9, 10, 11, 6, 8, 3, 5] Distance: 459.0

!!!!!YAY!!!!!! NEW SOLUTION Route: [0, 1, 7, 4, 2, 9, 11, 8, 10, 6, 5, 3] Distance: 449.0

!!!!!YAY!!!!!! NEW SOLUTION Route: [0, 1, 7, 4, 2, 9, 11, 10, 6, 8, 3, 5] Distance: 419.0

!!!!!YAY!!!!!! NEW SOLUTION Route: [0, 1, 7, 4, 2, 9, 11, 10, 8, 6, 5, 3] Distance: 408.0

!!!!!YAY!!!!!! NEW SOLUTION Route: [0, 1, 7, 4, 2, 9, 3, 5, 6, 8, 10, 11] Distance: 402.0

!!!!!YAY!!!!!! NEW SOLUTION Route: [0, 1, 7, 4, 2, 3, 9, 11, 10, 8, 6, 5] Distance: 385.0

!!!!!YAY!!!!!! NEW SOLUTION Route: [0, 1, 7, 4, 11, 10, 8, 6, 2, 9, 3, 5] Distance: 377.0

!!!!!YAY!!!!!! NEW SOLUTION Route: [0, 1, 7, 4, 5, 3, 9, 11, 10, 8, 6, 2] Distance: 374.0

!!!!!YAY!!!!!! NEW SOLUTION Route: [0, 1, 7, 4, 5, 6, 8, 10, 11, 9, 3, 2] Distance: 371.0

!!!!!YAY!!!!!! NEW SOLUTION Route: [0, 1, 7, 9, 3, 5, 4, 11, 10, 8, 6, 2] Distance: 363.0

!!!!!YAY!!!!!! NEW SOLUTION Route: [0, 1, 7, 9, 3, 2, 6, 8, 10, 11, 4, 5] Distance: 352.0

!!!!!YAY!!!!!! NEW SOLUTION Route: [0, 1, 7, 3, 5, 4, 11, 9, 2, 6, 8, 10] Distance: 350.0

!!!!!YAY!!!!!! NEW SOLUTION Route: [0, 1, 7, 3, 2, 9, 11, 4, 5, 6, 8, 10] Distance: 347.0

!!!!!YAY!!!!!! NEW SOLUTION Route: [0, 1, 7, 3, 9, 2, 4, 11, 10, 8, 6, 5] Distance: 345.0

!!!!!YAY!!!!!! NEW SOLUTION Route: [0, 1, 7, 3, 9, 2, 6, 8, 10, 11, 4, 5] Distance: 323.0

!!!!!YAY!!!!!! NEW SOLUTION Route: [0, 1, 7, 5, 3, 9, 2, 6, 8, 10, 11, 4] Distance: 322.0

!!!!!YAY!!!!!! NEW SOLUTION Route: [0, 1, 7, 5, 4, 2, 3, 9, 11, 10, 8, 6] Distance: 316.0

!!!!!YAY!!!!!! NEW SOLUTION Route: [0, 1, 7, 5, 4, 2, 6, 8, 10, 11, 9, 3] Distance: 313.0

!!!!!YAY!!!!!! NEW SOLUTION Route: [0, 1, 7, 5, 4, 11, 9, 3, 2, 6, 8, 10] Distance: 306.0

!!!!!YAY!!!!!! NEW SOLUTION Route: [0, 1, 7, 5, 4, 11, 10, 8, 6, 2, 9, 3] Distance: 302.0

!!!!!YAY!!!!!! NEW SOLUTION Route: [0, 1, 10, 11, 4, 5, 7, 3, 9, 2, 6, 8] Distance: 289.0

!!!!!YAY!!!!!! NEW SOLUTION Route: [0, 1, 10, 8, 6, 2, 9, 3, 7, 5, 4, 11] Distance: 286.0

!!!!!YAY!!!!!! NEW SOLUTION Route: [0, 1, 10, 8, 6, 2, 3, 9, 11, 4, 5, 7] Distance: 283.0

!!!!!YAY!!!!!! NEW SOLUTION Route: [0, 1, 8, 6, 10, 11, 4, 2, 9, 3, 7, 5] Distance: 274.0

!!!!!YAY!!!!!! NEW SOLUTION Route: [0, 1, 8, 6, 10, 11, 4, 5, 7, 3, 9, 2] Distance: 260.0

!!!!!YAY!!!!!! NEW SOLUTION Route: [0, 1, 4, 2, 6, 8, 10, 11, 9, 3, 7, 5] Distance: 259.0

!!!!!YAY!!!!!! NEW SOLUTION Route: [0, 1, 4, 11, 10, 8, 6, 5, 7, 3, 9, 2] Distance: 256.0

!!!!!YAY!!!!!! NEW SOLUTION Route: [0, 1, 4, 11, 10, 8, 6, 2, 9, 3, 7, 5] Distance: 248.0

!!!!!YAY!!!!!! NEW SOLUTION Route: [0, 1, 4, 5, 7, 3, 9, 11, 10, 8, 6, 2] Distance: 245.0

!!!!!YAY!!!!!! NEW SOLUTION Route: [0, 7, 5, 4, 1, 8, 6, 10, 11, 9, 3, 2] Distance: 236.0

Done.

Note that these random graphs are fully connected - every node connects to every other node.

Among the many interesting aspects of the problem, one of them is the impact of connectivity

on the solution time.

Another aspect of the problem is the topology of the network, and exploring how

a larger number of unconnected nodes, or groups of nodes clustered together but isolated from one another,

affect the final solution time and the final route.

But before get to that, we have some other things to work out.

Next Steps: Timing and Profiling

This post described a working implementation of a recursive backtracking solution

to the traveling salesperson problem on a graph. This is a naive solution, however,

and in the next few posts about the traveling salesperson problem we'll focus on using

timing and profiling tools for Java to profile this Guava program, identify bottlenecks,

and speed it up. In fact, there is one small tweak we can make to the algorithm covered above

that will improve the performance by orders of magnitude. But more on that in a future post.

Sources

-

"Traveling Salesman Problem". Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. The Wikimedia Foundation. Edited 12 March 2017. Accessed 23 March 2017.

<https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Travelling_salesman_problem>

-

"Seven Bridges of Königsberg". Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. The Wikimedia Foundation. Edited 11 March 2017. Accessed 23 March 2017.

<https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seven_Bridges_of_K%C3%B6nigsberg>

-

"The structure and function of complex networks". M. E. J. Newman.

<http://www-personal.umich.edu/~mejn/courses/2004/cscs535/review.pdf>

-

"Google Guava - Github". Alphabet, Inc. Released under the Apache 2.0 License. Accessed 20 March 2017.

<https://github.com/google/guava>

-

"Guava". Charles Reid. Edited 23 March 2017. Accessed 23 March 2017.

<https://www.charlesreid1.com/wiki/Guava>

-

"Graphs Explained". Google Guava Wiki. Accessed 23 March 2017.

<https://github.com/google/guava/wiki/GraphsExplained>

-

"Network". Google Guava API Documentation. Accessed 23 March 2017.

<http://google.github.io/guava/releases/snapshot/api/docs/com/google/common/graph/Network.html>

-

"Graph". Google Guava API Documentation. Accessed 23 March 2017.

<http://google.github.io/guava/releases/snapshot/api/docs/com/google/common/graph/Graph.html>

-

"Value Graph". Google Guava API Documentation. Accessed 23 March 2017.

<http://google.github.io/guava/releases/snapshot/api/docs/com/google/common/graph/ValueGraph.html>

-

"Google Java Style Guide". Alphabet Inc. Accessed 21 March 2017.

<https://google.github.io/styleguide/javaguide.html>